By Jennifer Doleac and Anita Mukherjee

The United States is grappling with an epidemic of opioid abuse and mortality. The U.S. Surgeon General recently called for everyone to carry naloxone — a drug that can save someone’s life if administered during an overdose. This call echoed similar advice by public health officials at the state and local levels. Over the past decade, states have gradually increased legal access to naloxone, which had previously required a prescription to obtain. The thinking is that if naloxone is in everyone’s medicine cabinet, then those suffering from opioid addiction will be more likely to survive an overdose. Surviving the overdose then allows them the opportunity to get treatment for their addiction.

We worried that increasing access to naloxone may do more than just increase the chances of surviving an overdose. When an activity becomes less risky, people are more likely to engage in it. (Economists call this moral hazard.) For instance, researchers have found that people became more likely to engage in risky sex after HIV became more treatable. It could be that when an opioid overdose is more easily treatable by naloxone, people are more likely to engage in risky opioid use. The goal of our recent study is to quantify this effect. We feel that we have achieved that goal. But we also generated an unintended side effect of a tremendous degree of outrage and opposition to our hypothesis and our results. We will first describe our results, and then discuss the controversy that followed their release.

To measure the effects of broad naloxone access, we looked at the repercussions of state laws that expanded access to naloxone. In their most generous form, these laws established a standing order that allowed anyone to walk into a pharmacy and purchase naloxone without a prescription; they also allowed community organizations to distribute naloxone widely. We measure the effects of these naloxone access laws on opioid-related ER visits, opioid-related crime, and opioid-related mortality.

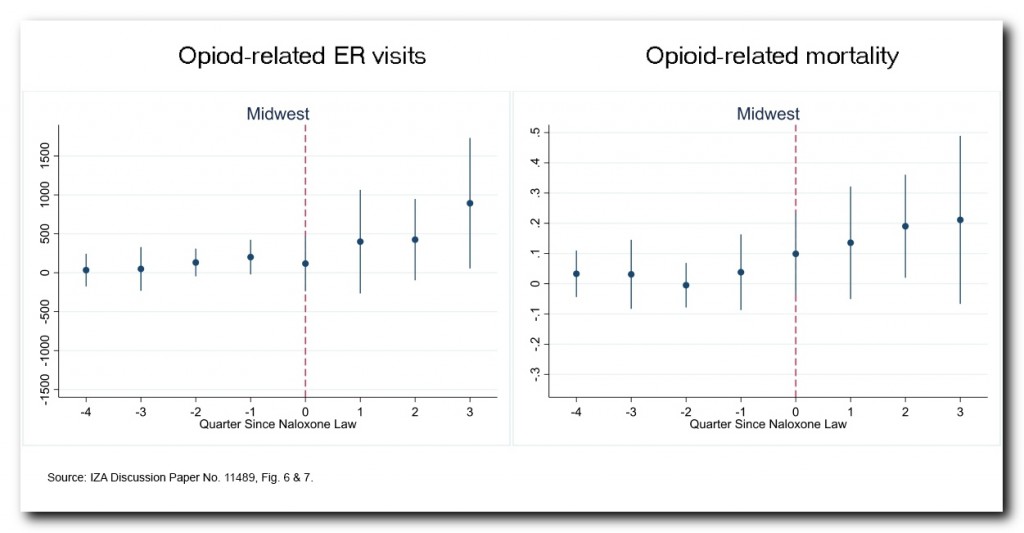

We find that, on average across the country, broadening access to naloxone led to more opioid-related ER visits and opioid-related crime, with no net reduction in opioid-related mortality. When we look specifically at the Midwest, the region hardest hit by the opioid crisis, we find that broadening naloxone access led to a 14% increase in opioid-related mortality. Our interpretation of this finding is that people are using opioids more often, and in more potent forms (e.g. fentanyl) when they have naloxone as a safety net.

Figure 1 plots the effects of broadening naloxone access on opioid-related ER visits and opioid-related mortality in the Midwest. As these graphs show, effects are flat and near-zero before the law change. This is comforting — if the trend started before the laws went into effect, this would suggest that it is not due to the laws themselves, but instead that the laws are in response to rising opioid abuse. At the effective date of the law, opioid-related ER visits and opioid-related mortality start to rise relative to states that didn’t have naloxone access laws go into effect on that date. The combination of no trend before the effective date and a trend after the effective date means that naloxone access laws are causing an increase in opioid abuse.

Figure 1 (from figures 6 & 7 in the paper)

The differences in effects across regions provide an opportunity to investigate what policies may reduce the unintended costs of naloxone access. We find suggestive evidence that greater availability of drug treatment may be important. That is, broadening naloxone access increases mortality more in places where less drug treatment is available. This makes sense if we think that the primary goal of naloxone is to give individuals a chance to get treatment for their addiction — if there is no treatment available, then perhaps it’s unsurprising if naloxone does more harm than good. This association between drug treatment availability and the effect of naloxone access laws suggests that investing in more drug treatment could help mitigate the unintended costs of broadening naloxone access.

The controversy

You can always count on economists like us to bring bad news to the policy conversation. But many policies don’t work as intended, and even effective policies involve tradeoffs. Knowing how deeply personal the opioid crisis is for many of us, we expected some pushback when we released the current paper — after all, many harm reduction efforts center on the widespread distribution of naloxone, and research documenting unintended effects would surely be unwelcome. But we also believe that our research findings contribute important information to discussions about how to address the opioid crisis. After presenting the paper at several conferences and seminars, and getting feedback from a variety of colleagues, we were confident that the results were ready to be shared more widely.

The debate around our paper was more heated than we expected. When we released the working paper in March, it was met with outrage from many people, primarily non-economists. We think that part of the negative reaction was caused by confusion over the term “moral hazard,” which is an economics term that (ironically) implies no moral judgment. But other pushback related to cross-disciplinary differences in theories about human behavior as well as empirical methods.

Some argued that moral hazard could not possibly operate in this context. Our view, shaped by theory and prior empirical research, is that such effects are plausible; we wanted to allow the data to tell us whether moral hazard was operating in this context rather than assume it. We began this project open to the possibility that moral hazard does not matter here, and we remain open to that possibility. But our analysis of the evidence leads us to believe that moral hazard is, in fact, present.

Others questioned our ethics as researchers (particularly in releasing a working paper before peer review, a common practice in economics) and our moral compasses as human beings. Our inboxes remain full of messages from people suggesting we’ve confused correlation with causation (in fact, identifying the causal effect was the key goal of this study), and even some instructing us on how to structure a research paper (as if we’re not experienced academics at major research universities).

Yet others wrung their hands about whether evidence of unintended consequences would lead policymakers to end access to life-saving medication, and suggested we should never have written a paper that could be easily “weaponized” by opponents of their preferred policy. We agree that academics have a responsibility to facilitate accurate interpretations of their research; we’ve tried to do that. But we don’t agree that academics should quash research results that don’t fit the narrative of one advocacy group or another. In subsequent conversations with policymakers and practitioners, we’ve been gratified that they recognize that even worthwhile policies involve costs as well as benefits. In our experience, decision-makers are thinking responsibly about what to do next, neither ignoring our evidence nor rashly calling for naloxone bans. Perhaps our critics should give them more credit.

Not all the reaction was negative, however. Many fellow academics took the time to read our paper and offer encouragement. Other people – including nurses, doctors, and others on the front lines of fighting the opioid epidemic – thanked us for doing this study and engaging in these uncomfortable conversations. Even those who questioned some of our findings denounced the personal attacks we received.

The reason economists disseminate working papers prior to peer review and publication is to have lots of smart people engage with the research, and we got plenty of that. The ensuing conversations — at conferences, on Twitter, in blog posts, and over email — helped us sharpen our thinking and come up with testable hypotheses related to concerns that were raised. Our study is better for it.

For instance, several people pointed out that, while we control for a variety of other opioid-related policies, our analysis did not control for state-level Medicaid expansions; these might have independently increased or decreased opioid abuse. We now show that controlling for Medicaid expansions has no impact on our results (and if anything, makes them stronger). Some questioned whether the effective dates of the laws we use are accurate. We reviewed the relevant legislation, clarified our definitions, and noted that in five states one could make a reasonable case that we should have used earlier dates (due to pilot policies at the county level, or related legislation that broadening naloxone access to at-risk populations). We show that when we use those alternate dates, the results are nearly identical to before.

Others wondered whether naloxone access laws are a good treatment variable in the first place — perhaps they did not have any meaningful effect on naloxone distribution. We emphasized that our study identifies an intent to treat effect: that is, we’re measuring the impact of the laws, which intended to increase access to naloxone, rather than the impact of naloxone itself. Our estimates will be biased toward zero if the laws had no effect on naloxone access — so the fact that we’re finding effects suggests the laws are indeed having an impact. Local data on naloxone distribution are typically unavailable, but we added some anecdotal evidence that the laws increased naloxone distribution in at least some places. Finally, discussions about the best way to present graphical evidence pushed us to switch from residual plots to coefficient plots. The graphs now show the effects of the access laws more clearly.

These new analyses, along with our previous robustness checks and placebo tests, make us confident that our study identifies the causal impact of naloxone access laws. We believe we have documented that broadening naloxone access increases opioid abuse. Our policy recommendations are (1) to consider these moral hazard effects when making naloxone more easily available, and (2) to implement policies that can help mitigate any unintended costs. For instance, invest more resources in drug treatment, and find ways to encourage those who have overdosed to get help. There won’t be a quick fix to this epidemic, but we hope that a better understanding of the effects of naloxone access will lead to better and more effective policies, and ultimately save lives.