“New Year’s Day: Now is the accepted time to make your regular annual good resolutions. Next week you can begin paving hell with them as usual.” — This quote attributed to Mark Twain describes what many people experience as they pledge to stop smoking, work out more often, or eat healthier. But why is it that so many of our New Year’s goals are short-lived?

“New Year’s Day: Now is the accepted time to make your regular annual good resolutions. Next week you can begin paving hell with them as usual.” — This quote attributed to Mark Twain describes what many people experience as they pledge to stop smoking, work out more often, or eat healthier. But why is it that so many of our New Year’s goals are short-lived?

According to psychologists and economists, lack of self-control causes people to make decisions they will later regret. Food consumption is a leading example of a setting in which self-control problems may play a role. Experimental evidence and the existence of a multi-billion dollar diet industry attest to this. However, there is limited direct evidence on self-control problems from observational consumption data because individuals’ food preferences are heterogeneous and may change over time or in response to changes in the economic environment.

A new IZA Discussion Paper by Laurens Cherchye (University of Leuven), Bram De Rock (University of Leuven), Rachel Griffth (University of Manchester), Martin O’Connell (Institute for Fiscal Studies), Kate Smith (Institute for Fiscal Studies) and Frederic Vermeulen (University of Leuven & IZA) fills this gap with empirical evidence on the existence, size and variation in self-control problems in food choice.

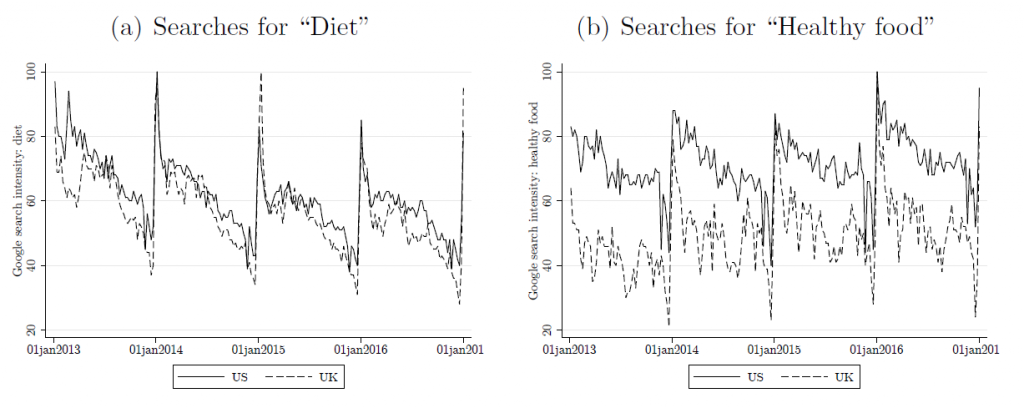

Google search trends reflect intentions to eat healthier

Internet search behavior can tell us a lot about people’s tendency to make (and fail to keep) New Year’s resolutions that would lead more healthy lifestyles: Time trends in Google searches for “diet” and “healthy food” show spikes in January and a steady decline as the year progresses.

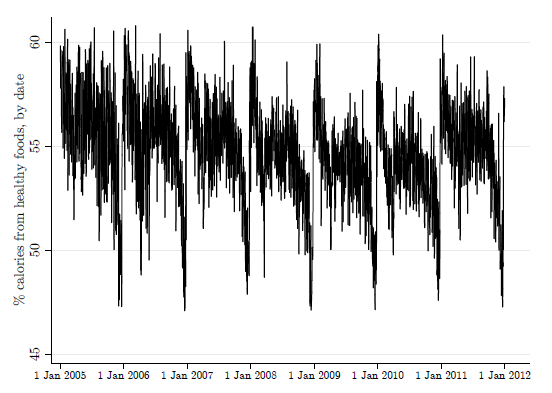

To find out whether this trend also exists in actual consumption behavior, the researchers exploit longitudinal data on the grocery purchases of a sample of 3,645 single individuals in the UK. The data record all grocery purchases at the transaction level made and brought into the home by these individuals. Using a nutrient profile score, the authors separate the purchased foods and drinks into “healthy” and “unhealthy” baskets.

Healthy January, unhealthy December

The analysis reveals how the share of calories from “healthy foods” varies over time on each day between 2005 and 2012. In line with the Google search pattern, there is a spike in healthiness in January, followed by some decline, plateauing around the middle of the year, then further declining until the end of the year.

From a theoretical perspective, the variation in diet quality within-person over time can be explained using a dual-self model, in which individual food purchase behavior reflects a compromise between a “healthy” and an “unhealthy” self. These two selves constantly bargain over the food budget and whether to buy fruits, vegetables or whole grains, or to buy unhealthy products such as soda, crisps and confectionery. Increases in the influence of the unhealthy self in decision-making thus indicates failure to exert self-control.

Just over half of calories from healthy foods

The empirical analysis also shows considerable variation in diet quality across individuals: 5% of individuals purchase more than 70% of their calories in healthy foods, while at the other extreme 5% buy less than 35% from healthy foods. On average, people purchase just over half (53%) of calories from healthy foods.

This variation is likely due to both preference heterogeneity and differences in the economic environment people face (such as food prices and budgets). It may also reflect persistent differences in individuals’ propensity to yield to temptation. The findings show that individuals with lower income experience greater variation in their spending on healthy foods, even after controlling for responses to price and budget changes. Younger people, on average, have more variation in their shopping baskets than older people.

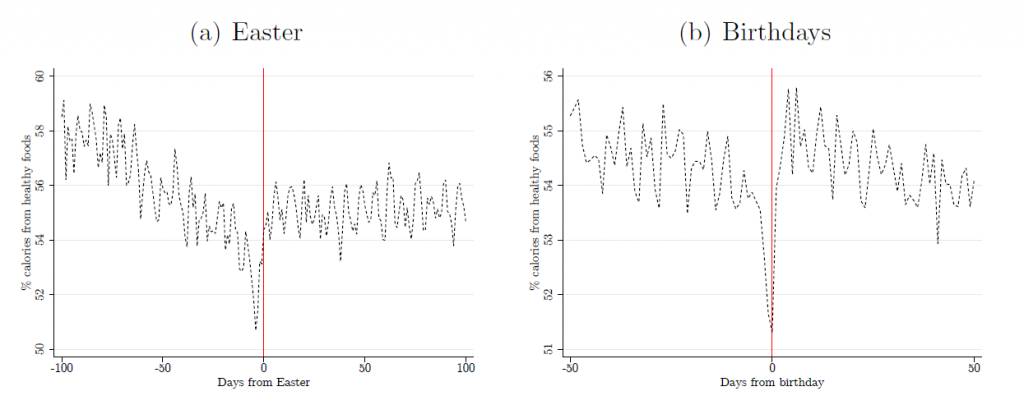

Systematic changes also around Easter and birthdays

Easter and own birthdays are two other times of the year which are also associated with systematic changes in purchases of healthy foods. In the run up to these dates, the share of healthy foods purchased tends to decline, gradually over several days in the former case and more starkly a few days beforehand in the latter case. In both cases, the share of calories from unhealthy products recovers towards the pre-event level immediately following the occasion.