By Arnaud Chevalier and Olivier Marie

By Arnaud Chevalier and Olivier Marie

Do individuals born at different points of the economic cycle have different outcomes, and what could be the reasons? To answer this question, we explore the educational attainment and criminal activity of children born in East Germany, in the few years after the collapse of the Berlin Wall when uncertainty about the future was extremely high. We first discuss how such economic circumstances could affect parenting decisions of individuals differently depending on their characteristics and thus lead to cohort selection. We then provide empirical evidence on selection looking both at the child’s outcome and at the mechanisms which may have led to them.

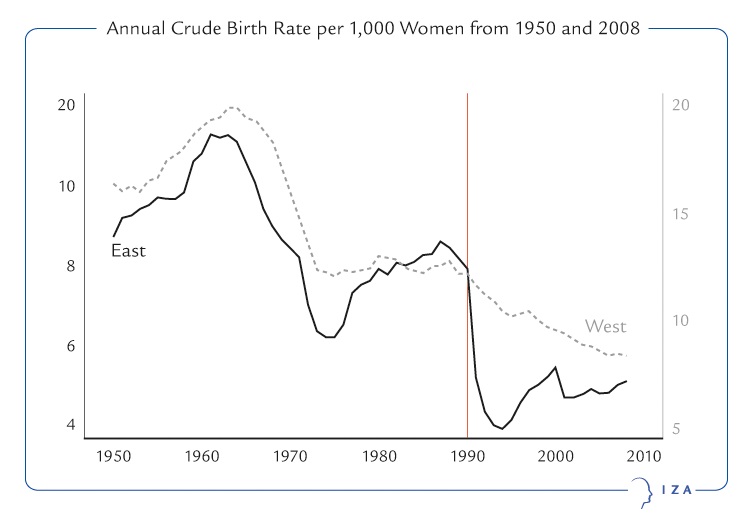

This November, Germany and the rest of Europe celebrate the twenty fifth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall which was perhaps the most symbolic moment of the collapse of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe. This event had colossal repercussions in the economic development of the region but also, and maybe less obviously, on its demography. Following the collapse of the Communist regimes, fertility in Eastern Europe went into a sharp decline. This was especially marked in East Germany which over a very short period experienced a 50% drop in fertility (see figure below) which has been described by demographers as the “most substantial fall in birth rates that ever occurred in peacetime”.

Economic uncertainty was one of the main reasons for the fertility drop. Which kind of parents decide to still have children in these distressing economic times, and does this parental selection matter in terms of the cohort outcomes? Theoretically, an economic downturn has two opposite effects on the demand for children, it reduces household income (income effect) but it also reduces the opportunity costs of having children (substitution effect). Which effect dominates is a priori ambiguous, but since fertility is pro-cyclical, the income effect appears to dominate overall. In fact, it is likely that the relative size of the substitution and income effect depends on family characteristics, leading to differences in parental composition throughout the economic cycle. Indeed, a 2004 study shows that in the U.S. white mothers giving birth when unemployment is higher are less educated resulting in worse health outcomes at birth.

The fall of the Berlin Wall provides a unique “natural experiment” to study this question. In our 2013 paper we define the cohort of children born in East Germany between August 1990 (conceived just after the collapse of the wall) and December 1993 as the “Children of the Wall”. We provide evidence on parental selection based on i) the average criminal activity of the Children of the Wall as they grew up, ii) their educational attainment and iii) detailed individual level data, on both mother and child, regarding parental skills.

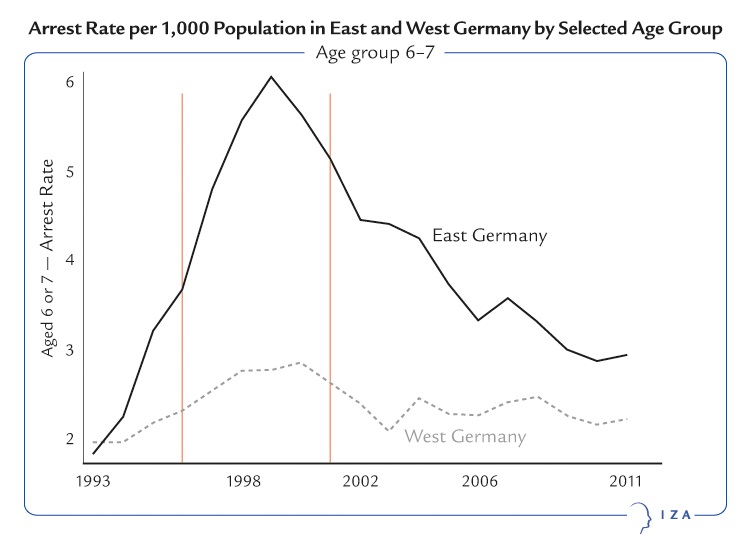

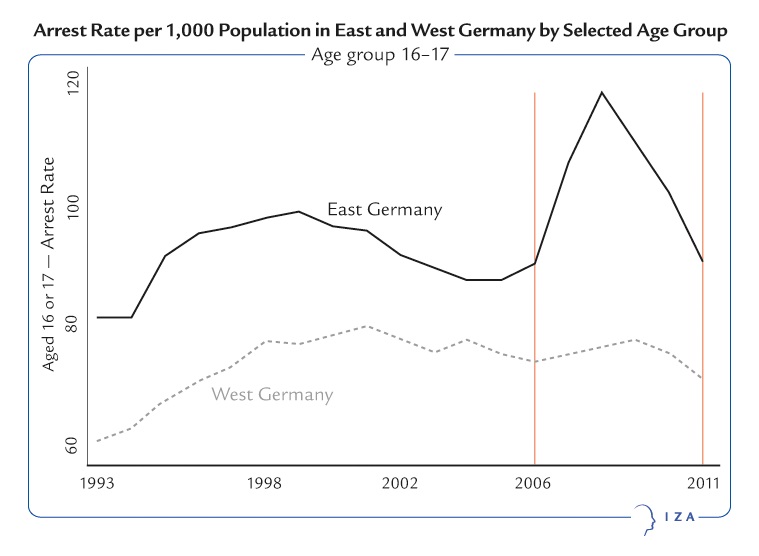

Using state level statistics on contact with the police by age group over the period 1993-2011, we find that the Children of the Wall exhibit arrest rates at least 40 percent higher when compared to older cohorts and to their West German peers. This is true for all crime types and for both boys and girls. Importantly, these differences in the frequency of contact with the police start appearing as early as age 6 (see figure below). This is despite being part of a numerically smaller cohort, which is usually associated with positive outcomes and is indicative of a strong negative parental selection.

Vertical red lines indicate the Children of the Wall cohort.

Similarly, the children of the Wall have worse educational outcomes. Compared to their class peers who were conceived just before the wall fell, they have lower test scores in PIRLS (age 11-12) and PISA (age 15-16) and are over-represented amongst low achievers. As such, they are 33% more likely to have repeated a grade by age 12 and 9% more likely to have been put into a lower educational track.

To explore if these negative outcomes are driven by negative parental characteristics, we make use of very detailed survey data from the German Socio Economic Panel (SOEP) and the Deutsches JugendInstitut survey (DJI). Women who gave birth in East Germany just after the end of the communist regime were on average younger, less educated, less likely to be in a relationship and less economically active. Importantly, they also provided less educational input to their children even if they are not poorer. The Children of the Wall also rate their relationship with their mothers and the quality of parental support they have received by age 17 much less favorably than their peers. Both these children and their mothers are also far more risk-taking than comparable individuals who did not give birth (were not born) in East Germany between August 1990 and December 1993.

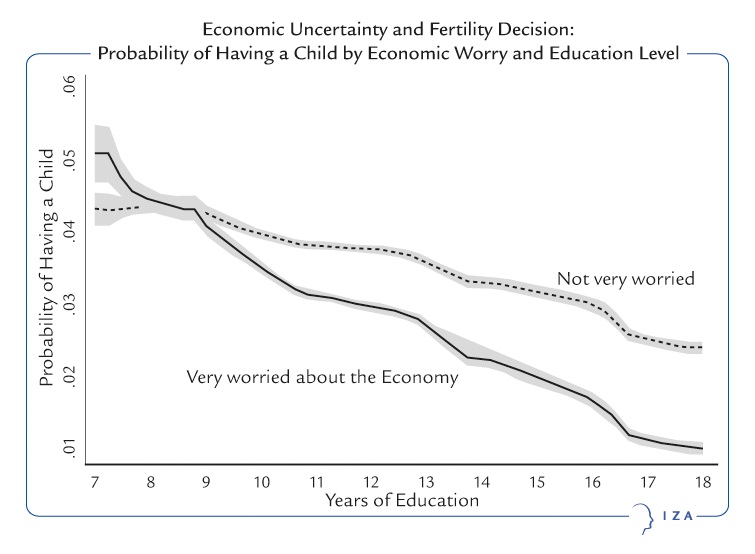

While these results are in line with negative parental selection, they could also be driven by timing of birth effects: Due to the economic turmoil prevalent at the time, these children may have experienced higher levels of maternal stress in utero and during early childhood, which may have shaped their future behavior. To assess this hypothesis, we examine the same set of outcomes for the older siblings of the Children of the Wall who were born in the non-uncertain times of East German Communism. They also similarly report having a poor relationship with their mothers, lower educational attainment, and are more risk taking individuals. We thus reject the possibility that the Children of the Wall have worse outcomes due to being born in ‘bad times’ and instead conclude that the negative outcomes observed for this cohort are explained by the lower average parenting skills of those who decided to have children during a period of high economic uncertainty. A possible reason for this negative parental selection is that the fertility decision of these women does not react as strongly to changes in the economic environment. Indeed, further analysis of the SOEP reveals that, less educated mothers are far less l

ikely than more educated one to reduce their fertility when they perceive a bad economic environment (see figure):

Our findings confirm that parental selection may be one of the best predictors of the future outcome of a cohort, and that this most likely works through quality of parenting. These conclusions have potentially important policy implications. First, provision of public services should not only be based only on the size of an incoming cohort, and more attention should be paid on its composition. Second, interventions need to start from a very young age, and targeting could probably be improved by more commonly including non-cognitive characteristics such as risk attitude of expecting mothers or children.