A fundamental question in labor economics is how wages are determined. To shed light on this, we can ask a smaller but tractable question: Why are so many wages round numbers? This might seem trivial, but actually, round-numbered wages (like $40,000 or $50,000) make up a disproportionate share of all wages—much larger than what standard economic models predict. Therefore, understanding this pattern can teach us about how companies decide what to pay their workers.

This puzzling behavior can be explained by non-standard behavior of workers (e.g., firms may pay round-numbered wages to exploit worker behavioral biases, such as left-digit bias) or by non-standard behavior of firms. A recent IZA discussion paper by Germán Reyes, which is now forthcoming in the Review of Economics and Statistics, shows that this wage bunching is partly driven by firms’ non-standard behavior, specifically their uncertainty about the fully optimal salary. The study provides evidence that many firms use simple heuristics and round numbers when setting wages, a practice the author calls “coarse wage-setting.”

Wage clustering around round numbers

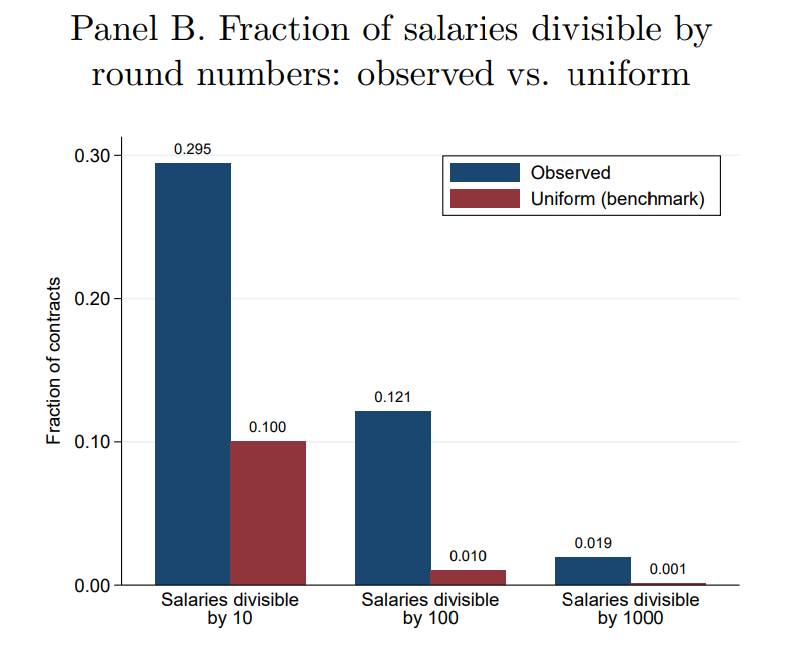

Using data from over 200 million new hires in Brazil, the study establishes that contracted salaries tend to cluster at round numbers. About a third of new hires’ contracted salaries are round numbers (as a benchmark, the share would be 10 percent if the last digit of wages was uniformly distributed). Some firms (named “bunching firms”) hire workers exclusively at round-numbered salaries.

To understand what drives bunching firms to pay round-numbered salaries, the study explores several key questions:

- What are the characteristics of these bunching firms? They tend to be younger, smaller, have less hiring experience, are less likely to have an HR department, and their managers have fewer years of schooling—all characteristics typically associated with less sophisticated business practices.

- Do bunching firms have better market outcomes (as one might expect if the wage-setting was to exploit a worker bias)? The answer is no. These firms tend to experience worse outcomes, including higher employee turnover, lower job growth rates, and a lower survival rate.

- Do bunching firms behave in “non-standard” ways in other decision-making contexts? Yes, they do. These firms also rely on coarse figures for salary increases, such as using integer percentages or round monetary values.

Understanding coarse wage-setting

These results suggest that bunching firms don’t pay round salaries to exploit a worker bias. An alternative explanation is they pay round-numbered salaries as a simple but coarse approximation because they simply don’t know what the fully-optimal salary is. Indeed, when hiring a new worker, firms face considerable uncertainty about a worker’s productivity, a key factor in determining the ideal wage.

Estimating a worker’s productivity requires answering complex questions: What are all of the possible tasks that the new hire will perform? How does each of these tasks affect the firm’s bottom line? How likely is the prospective employee to successfully accomplish each of these tasks? Answering these questions is challenging not only for occupations that involve varying and unstructured tasks—such as a neuroscientist or a physician—but even for relatively regimented jobs, such as a security guard or a truck driver.

Rather than gathering all the information needed to compute worker productivity, some firms may rely on rules of thumb or heuristics—a practice the paper calls “coarse wage-setting.” The study develops a model based on this idea and finds support for its predictions.

Implications of coarse wage-setting

The findings of this study have implications for our understanding of labor markets and economic policy. Since round-numbered wages make up a disproportionate share of all wages, understanding this phenomenon sheds light on overall firm wage-setting practices and can inform economic models. Research methods that infer parameter values from firm optimality conditions might yield biased estimates due to coarse wage-setting. Finally, coarse wage-setting can have downstream consequences for important economic outcomes, like within-firm wage inequality or wage stickiness.