Electronic self-service platforms can help job-seekers find suitable vacancies and facilitate self-development. But the results of a recent research project by Bert Van Landeghem, Frank Cörvers and Andries de Grip presented in a new IZA Discussion Paper remind us that a “human touch” is crucial to get everybody on track, and to prevent some people from entering the vicious circle of long-term unemployment.

Electronic self-service platforms can help job-seekers find suitable vacancies and facilitate self-development. But the results of a recent research project by Bert Van Landeghem, Frank Cörvers and Andries de Grip presented in a new IZA Discussion Paper remind us that a “human touch” is crucial to get everybody on track, and to prevent some people from entering the vicious circle of long-term unemployment.

“Self-service” platforms have rapidly developed as a new low-cost way to offer counseling and information services to the unemployed in many countries. This has obviously many advantages for both clients and providers. Job seekers can browse through online vacancies with powerful search tools that help them match the skills listed in their online CV with the requirements for available jobs.

Saving at the wrong end

However, in times of austerity, governments see such tools as a way to economize on job coaches. They encourage people to do everything online and reduce face-to-face coaching for those who have just become unemployed, reserving more costly counseling for the long-term unemployed. Some people might however need some coaching to get on track, and there is a danger that mistakes or missing information in CVs are detected much too late. Finally, there is also a psychological side to it: some people will need human encouragement to get going after the disappointment of losing a job.

To investigate the importance of offering some kind of human coaching right after the start of the unemployment spell, Van Landeghem, Cörvers and de Grip implemented a test with a Public Employment Office in the Belgian region of Flanders. There, at least until recently, all unemployed between the age of 25 and 50 were invited to a mandatory collective information session.

Benefits of “human touch” outweigh the costs

Divided up in groups of up to 30 individuals, they received information about the activity of the employment office, training possibilities and employer subsidies. Next, the employment agency’s website with all its tools was explained, after which clients were invited to use a workstation and update their own online profile and preferences. At the end of the session, every client did a short one-on-one interview with one of the two present coaches.

Due to the long waiting list for this information session, the researchers randomly split up the list in two groups. One group was invited straight after becoming unemployed (within the first weeks), while the others were only invited four to five months after having registered as unemployed. They found that being invited very early proved beneficial for workers’ employment chances. Especially the low-educated who were invited immediately after becoming unemployed had worked 4.7 days more in the four months after the day of becoming unemployed than low-educated workers who were left alone for a while.

In the end, the authors of the IZA paper were able to confirm the positive effects of early collective information sessions for the unemployed. In terms of room rental and staff costs they are relatively cheap, and looking at the benefits it is clear that these far outweigh the costs.

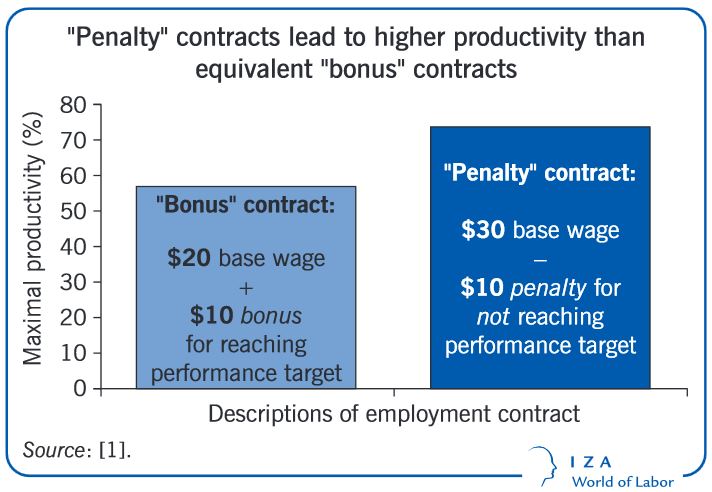

A large empirical literature supports the view that linking payment to performance is highly effective in raising productivity. However, often little attention is paid to how performance incentives are implemented in employment contracts. While most employers work with bonuses, some also arrange penalty contracts that set a base wage, part of which can be lost if performance targets are not reached.

A large empirical literature supports the view that linking payment to performance is highly effective in raising productivity. However, often little attention is paid to how performance incentives are implemented in employment contracts. While most employers work with bonuses, some also arrange penalty contracts that set a base wage, part of which can be lost if performance targets are not reached.

The standard empirical evaluations of labor market policy only consider the direct effects of single programs on their participants. This column* (based on

The standard empirical evaluations of labor market policy only consider the direct effects of single programs on their participants. This column* (based on  Notes: Effects are expressed in percent of average monthly earnings within 3.5 years after unemployment (3547 CHF = 3290 EUR = 3575 USD in sample). Treatment effects: effects of being exposed to at least one carrot (job search assistance, training) or stick (sanction, workfare program). Regime effects: marginal effect of changing policy intensity by 0.1.

Notes: Effects are expressed in percent of average monthly earnings within 3.5 years after unemployment (3547 CHF = 3290 EUR = 3575 USD in sample). Treatment effects: effects of being exposed to at least one carrot (job search assistance, training) or stick (sanction, workfare program). Regime effects: marginal effect of changing policy intensity by 0.1. Notes: Marginal effects of changing the regimes by 0.5 standard deviation (i.e., about 0.1 in policy intensity). Earnings changes: in percent of average monthly earnings of non-treated individuals. Cost changes: in percent of total benefit cost per person.

Notes: Marginal effects of changing the regimes by 0.5 standard deviation (i.e., about 0.1 in policy intensity). Earnings changes: in percent of average monthly earnings of non-treated individuals. Cost changes: in percent of total benefit cost per person. What many have already suspected has now been scientifically proven: Employers are screening job candidates through Facebook. In fact, your Facebook profile picture affects your callback chances about as strongly as the picture on your resume. This is the finding of a

What many have already suspected has now been scientifically proven: Employers are screening job candidates through Facebook. In fact, your Facebook profile picture affects your callback chances about as strongly as the picture on your resume. This is the finding of a  The study by

The study by  Environmental policy pertaining to air pollution has been estimated to have large health benefits. However, these policies also come with costs. Production is typically reallocated away from newly regulated industries to other sectors and locations, and this creates a broad set of private and social costs. In terms of labor inputs, this reallocation is often framed in terms of “jobs lost,” and the distinction between “jobs versus the environment” is one of the more politically salient aspects of these regulations.

Environmental policy pertaining to air pollution has been estimated to have large health benefits. However, these policies also come with costs. Production is typically reallocated away from newly regulated industries to other sectors and locations, and this creates a broad set of private and social costs. In terms of labor inputs, this reallocation is often framed in terms of “jobs lost,” and the distinction between “jobs versus the environment” is one of the more politically salient aspects of these regulations. Human development starts early, and neuroscientists point to the first three years of brain development as especially consequential. Foundations for academic and social success later in life are created through the experiences in children’s earliest years.

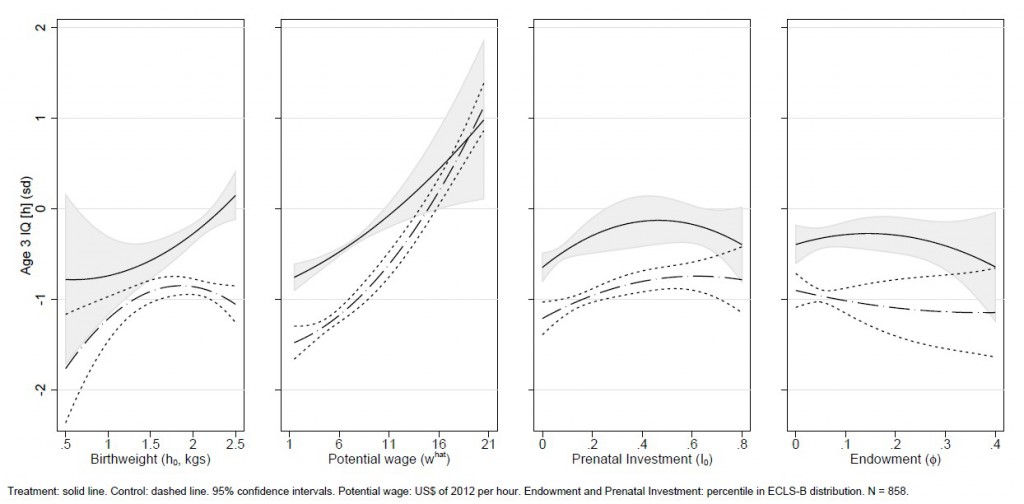

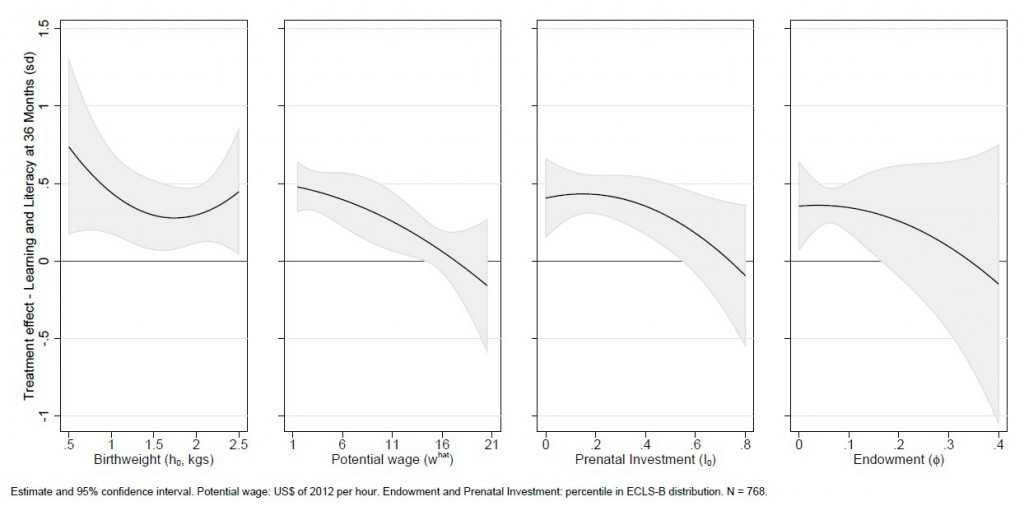

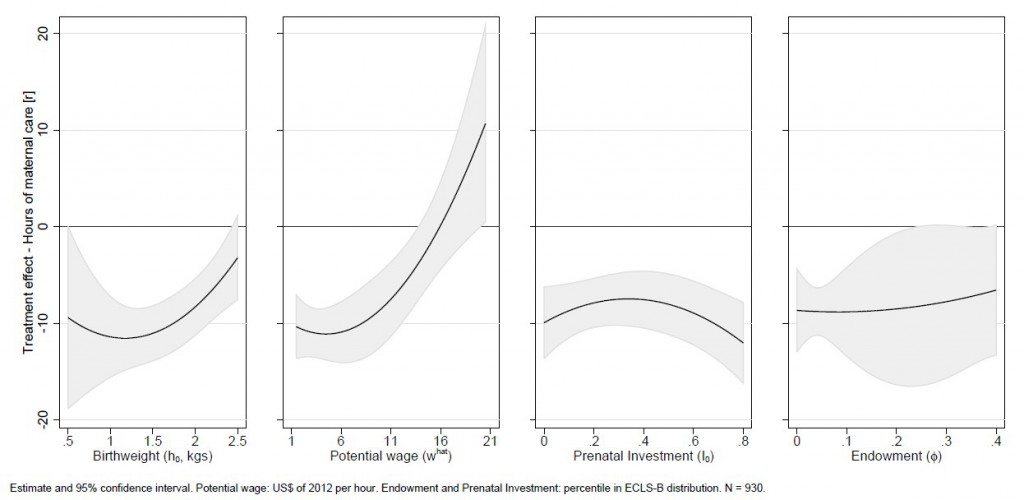

Human development starts early, and neuroscientists point to the first three years of brain development as especially consequential. Foundations for academic and social success later in life are created through the experiences in children’s earliest years.

increasingly cognizant of the long-term consequences of student absenteeism and suspensions, which are particularly troubling given that absence and suspension rates are significantly higher among low-income and racial minority students. However, while credible evidence of the harm caused by primary school absenteeism

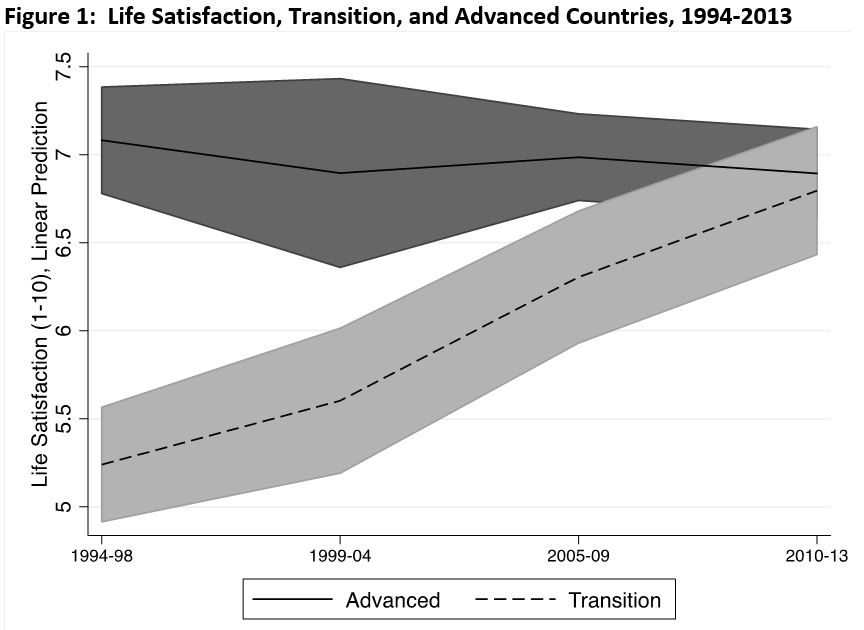

increasingly cognizant of the long-term consequences of student absenteeism and suspensions, which are particularly troubling given that absence and suspension rates are significantly higher among low-income and racial minority students. However, while credible evidence of the harm caused by primary school absenteeism  integration and digital communication are undoubtedly bringing people closer together. But do they also cause the levels of satisfaction to converge? Researchers have long studied the institutional factors contributing to the strong international differences in life satisfaction.

integration and digital communication are undoubtedly bringing people closer together. But do they also cause the levels of satisfaction to converge? Researchers have long studied the institutional factors contributing to the strong international differences in life satisfaction.

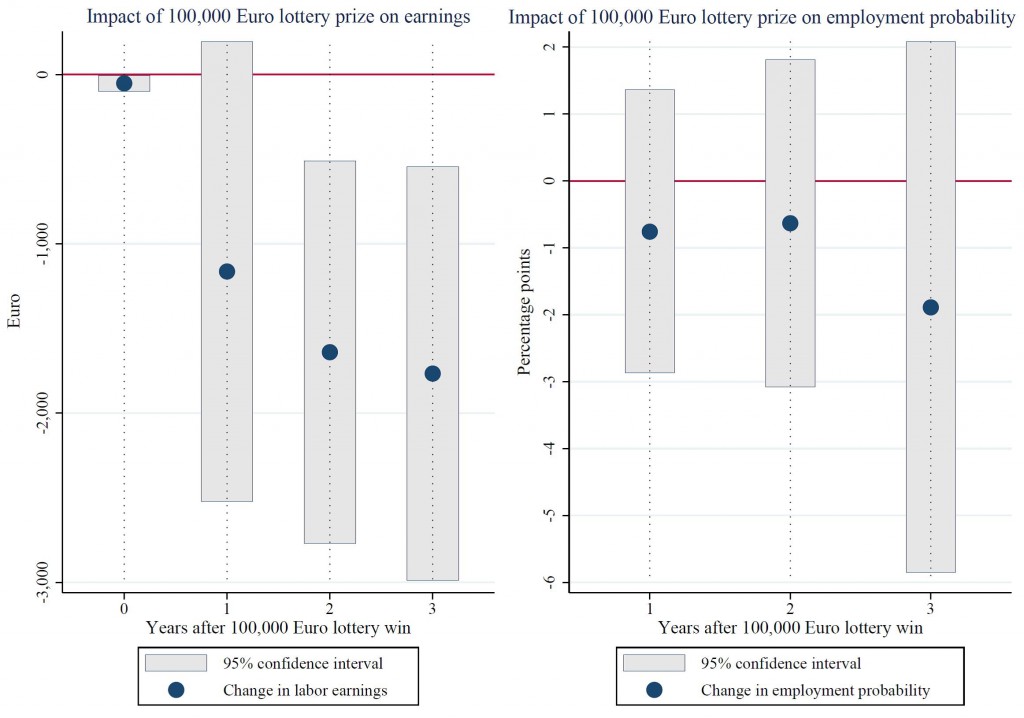

Economic theory provides ambiguous predictions about the effect of wage increases on the allocation of time between leisure and work. On the one hand, a wage increase makes the individual richer, lowering the preferred hours of work. On the other hand, higher wages raise the opportunity cost of not working (the money one could have earned instead of spending time for leisure), pushing up the preferred number of working hours.

Economic theory provides ambiguous predictions about the effect of wage increases on the allocation of time between leisure and work. On the one hand, a wage increase makes the individual richer, lowering the preferred hours of work. On the other hand, higher wages raise the opportunity cost of not working (the money one could have earned instead of spending time for leisure), pushing up the preferred number of working hours.

The effects of the minimum wage on youth employment flows are at the focal point of the current policy debate in the Netherlands. A specific feature of the Dutch minimum wage system is that the youth minimum wage rate is increasing with a worker’s calendar age. Workers become eligible for the minimum wage on their 15th birthdays, being paid approximately 30% of the adult minimum wage rate. The applicable rate increases each year, until the adult level is attained at the age of 23.

The effects of the minimum wage on youth employment flows are at the focal point of the current policy debate in the Netherlands. A specific feature of the Dutch minimum wage system is that the youth minimum wage rate is increasing with a worker’s calendar age. Workers become eligible for the minimum wage on their 15th birthdays, being paid approximately 30% of the adult minimum wage rate. The applicable rate increases each year, until the adult level is attained at the age of 23.