By Werner Eichhorst and Paul Marx

To mitigate the labor market impact of the Corona recession, the European Commission has proposed to the Council a temporary European financial instrument (SURE, Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency). Its goal is to support short-time work and related emergency schemes in EU member states most affected by the crisis.

This instrument, based on art. 122 TFEU, is to be funded through bonds issued by the EU up to 100 billion euros. The supporting funds will be handed over as loans under favorable conditions to those member states suffering heavily from the crisis and using short-time work (or similar measures, particularly for the self-employed) to secure employment and income.

The distribution of the funds depends upon decisions by the Council, upon proposal by the Commission. To this end, the Commission will have to assess requests from the member states and evaluate their situation, in particular the increase of spending on short-time work and similar measures.

While it is conceived as a temporary assistance to member states, there is no fixed end date due to the unpredictable development of the current emergency. However, the scheme will be limited by the available funds. It will be complementary to existing or planned national measures and to other European funds.

SURE can be seen as an ad-hoc European reinsurance of national short-time work schemes. To understand the proposal, two levels have to be distinguished: 1) the general role of short-time work and 2) the genuine European contribution.

Sharing the financial burden of unemployment

Short-time work is a partial unemployment scheme, compensating for hours not worked and not paid due to an inevitable and temporary loss of demand (read more in the IZA World of Labor). The current shutdown of some sectors is a textbook example for its use. It allows for a burden sharing between employers, employees and unemployment funds or government (the exact distribution depends, of course, heavily on the details of the schemes).

It relieves employers from part of the labor cost during the slump, thereby trying to avoid dismissals, maintain employment and stabilize the labor force so that firms can catch up quickly during a phase of economic recovery. Short-time work only makes sense if one can expect a return to ‘normal’ economic activity and increased labour demand in the near future. This is a plausible assumption in the unexpected and (hopefully) temporary Covid-19 recession.

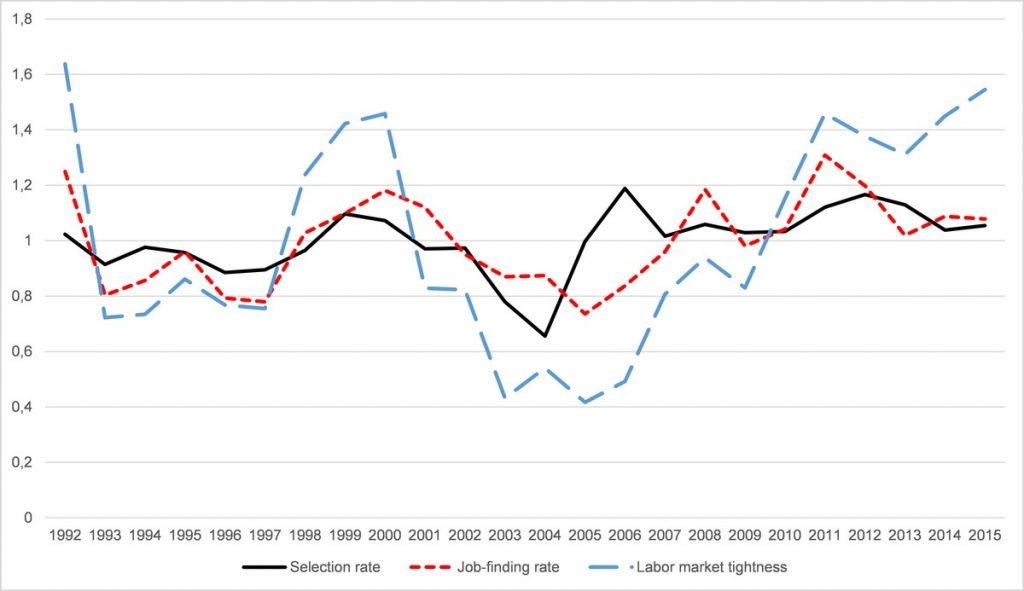

Ideally short-time work schemes provide assistance to firms and workers for as long as the emergency situation lasts. SURE is arguably inspired by the remarkable success of the German short-time work scheme (Kurzarbeit) during the 2008/09 crisis, where it helped avoid job losses in the heavily exposed export sector. It is important to note, however, that the success of Kurzarbeit benefited from a tradition of social partnership in large industrial firms that provided additional working-time and wage flexibility.

Covid-19 crisis differs from previous crises

Now, the situation in Germany and elsewhere is different. The Covid-19 crisis not only affects manufacturing but many small and medium-sized firms in the service sector as well as the self-employed. In these cases, short-time work (and assistance to self-employed outside unemployment insurance) can only work if it is administered in a way that facilitates access by target groups that have no experience with this scheme.

This creates strong demands on the responsible administrative bodies. Hence, while we know that some countries have created or expanded short-time work in response to the 2008/09 crisis and are going even further in the current situation, it will be crucial to what extent the newly affected firms and freelancers can effectively be supported. This might create a dilemma in some countries, because public employment services have to decide between effective monitoring (which will compromise the stabilizing function of the scheme) and a lenient approach (which will make it hard to prevent deadweight losses).

It is noteworthy that for the case of German industry, the application for Kurzarbeit typically requires consent from works councils. This is an additional control mechanism that is absent in countries and sectors with different patterns of industrial relations.

One should also take into account the difficult situation of workers with fixed-term contracts and temporary agency workers. It is the raison d’etre of these jobs to provide flexibility in times of crisis. The experience of 2008/09 tells us that these workers, unsurprisingly, suffer disproportionately from economic shocks.

Short-time work complements dismissal protection

In this context, it is important to appreciate that short-time work is ideal to complement dismissal protection. It allows employers to retain workers at low cost instead of having to shoulder separation costs in the form of severance pay, long notice periods, or law suits.

Temporary workers do not create separation costs and tend to be excluded from this beneficial complementarity. Few employers will extend temporary contracts or assignment of agency workers only to use short-time work. Short-time work therefore risks leaving behind workers that are already vulnerable. An explicit approach to protecting these groups would make the initiative more socially balanced. This is important in particular for the segmented labor markets that exist in some of the heavily exposed countries.

SURE is a timely and necessary expression of European solidarity.

SURE is a timely and necessary expression of European solidarity with the member states, firms and workers that are affected by the crisis in an unprecedented way. There is a short- and medium-term dimension to this. In the short run, the European contribution relieves immediate pressure on national budgets and unemployment funds. Of course, is too early to tell if the funds are sufficient to make a difference and if the national administration can deliver short-time work quickly enough to those in need.

The European initiative does not directly interfere with the diversity of national schemes. Nor is there are an agreement on the precise goals of the intervention. While this is justified by the time pressure involved, it would be important to ensure that European funds do not simply crowd out national spending, but lead to a genuine expansion. This applies in particular to the question of how generous and inclusive national systems are towards low-wage earners, workers on non-standard contracts or vulnerable, economically dependent self-employed.

Hence, the increase in expenditure for short-time work and similar programs that is required to be supported by European loans should also be linked with a sufficient generosity and scope of these programs.

Model for a European unemploymen (re)insurance

Second, in a mid- to long-term perspective, the proposed scheme could not only help stabilize member states’ labor markets now, but also provide a pilot for the introduction of a permanent European unemployment (re)insurance system. The current crisis illustrates how valuable an effective system of automatic stabilizers without the need for cumbersome ad-hoc decision making would be.

Based on our experience with previous crises, the European initiative to expand short-time work is a sensible policy that can help alleviate the Covid-19 shock. Beyond the current crisis, it could be an opportunity to address the pressing questions of how we could organize European solidarity – and how we want to include workers at the margins of Europe’s current employment models.