Productivity growth in the UK has conspicuously lagged behind that of other G7 nations since the global financial crisis. The latest quarterly figures perpetuate what has come to be known as Britain’s “productivity puzzle”.

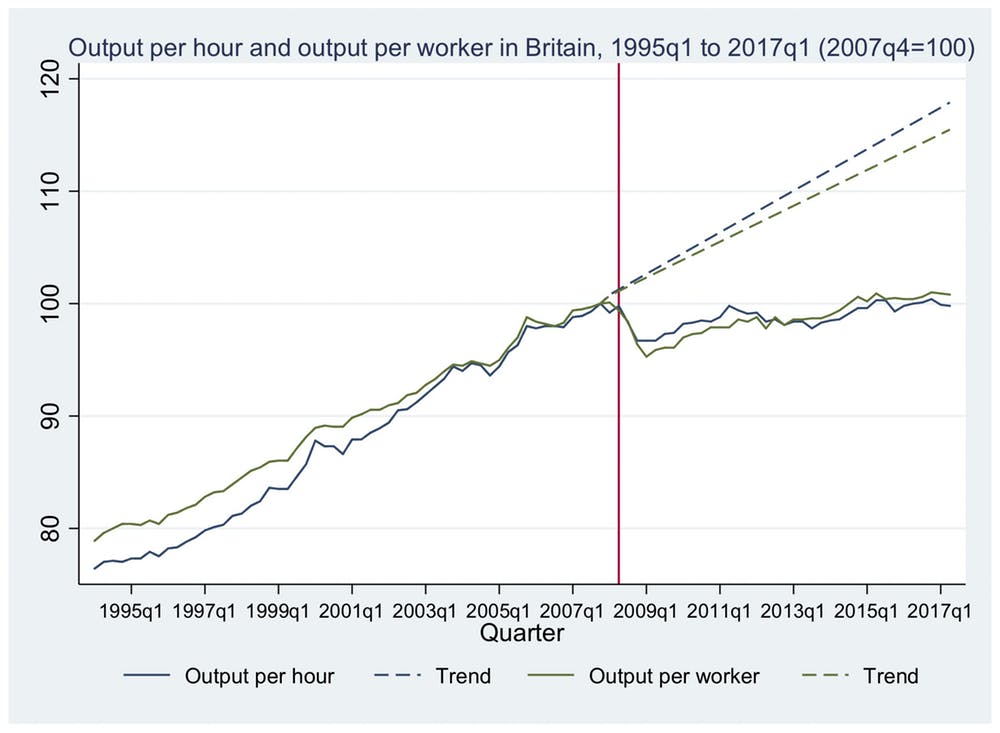

This flatlining of productivity has been unprecedented in the post-war era. Productivity (which measures output per hour and/or output per worker) would have been 16% higher by 2015 if the pre-recession level of productivity had been maintained. That this productivity slump has endured well beyond the financial crisis has become a major policy concern given that the pace of productivity growth determines a nation’s material well-being.

Meanwhile, efforts to jolt the patient back to life have taken on an especially urgent air in the face of Brexit. The fear of a “talent exodus” in the wake of Britain’s withdrawal from the EU, coupled with a possible restriction on migrant flows and the impact this might have on business, has set alarm bells ringing.

So, too, have the reality of accelerated technological change and the consequent potential mismatch between the skills that employees possess today and the skills that they are likely to need in the future. Small wonder that every major political party has called for better training and an improvement in the skills of the UK’s existing workforce. It is well established that an improvement in skills helps boost productivity.

But how is this upskilling best achieved? Government-backed efforts currently revolve around the Investors in People standard, which is a benchmark for good training and staff development in organisations. Companies that sign up to the initiative and meet its guidelines are rewarded with an accreditation.

With Brexit on the horizon and the productivity puzzle persisting, we seem to be rapidly nearing the point at which the effectiveness of this voluntary scheme is called into question or requires further investment.

Embracing the upskilling effort

The Investors in People initiative has assisted thousands of businesses since its launch in 1991 – more than 10,000 over the last 27 years. And my recent IZA discussion paper looking at its effectiveness shows that it brings businesses genuine benefits in terms of workforce upskilling – and so also benefits the wider economy.

I examined data from the Workplace Employment Relations Survey, a national survey of all UK businesses with five or more employees, which gives a comprehensive picture of organisations’ attitudes to workforce training. The data include responses to questions related to different aspects of on-the-job training, such as computing, teamwork, leadership, problem solving and customer service. Analysing these and focusing on almost 900 panel organisations in the 2004 and 2011 surveys, there was a clear and positive link between the Investors in People accreditation and upskilling in the private sector.

This is solid evidence that the initiative is effective. In particular, it was linked with helping organisations train staff in soft skills such as teamwork and communication and more practical ways of boosting productivity such as computer training and operating new equipment.

On-the-job training, at least in the short term, is therefore one of the most plausible policy tools available for overcoming the UK’s poor productivity growth, preparing for a challenging Brexit and the growing skills shortage that this could exacerbate.

Upscaling upskilling

Despite the clear success of the Investors in People initiative and the number of businesses it has helped, logic alone dictates that many thousands more have had nothing to do with it. The number of UK small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) alone is thought to be more than five million.

The idea of making the Investors in People and similar initiatives compulsory sounds impractical – accommodating five million accreditation-seeking businesses seems fanciful. But with pressure to improve the skills of the UK’s existing workforce never so intense, there’s a need to ensure upskilling takes place on a truly significant scale.

Upskilling initiatives will not entirely solve the productivity puzzle. But it is a good start and best applied to the private sector. The public sector, which includes the NHS, consumes a significant amount of public resources and yet struggles to meet the demand for its services. It is in desperate need of a productivity boost, particularly given its reliance on EU workers. Yet, my research found that the Investors in People accreditation was not as effective in improving skills in the public sector. It may therefore need its own specially-designed upskilling programme.

Needless to say, solving the UK’s productivity puzzle is a daunting prospect. But the evidence around upskilling shows that at least some of the country’s problems can be fixed through rolling out more training programmes. The talent is there. It needs to be better developed.

Note: This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.![]()