By Carol Graham and Milena Nikolova

The recent economic crisis and the subsequent lagging economic recovery renewed the immigration debate in the United States and beyond. While there are benefits from migration for the recipient economies, there are also potential costs, which range from concerns about migrants adding to the ranks of welfare systems, to threats to the jobs of natives, to the difficulties of assimilating migrants from different countries and cultures. On balance, migration’s benefits for the destination economies outweigh the costs: immigrants are net contributors to public coffers and complementarities between low-skilled immigrants and natives may exist, particularly when new migrants take low-skilled jobs that native workers eschew. While the effect of migration on the well-being of native populations is important, so is the question of how migrants fare once they reach their destination countries.

In part, this is because of the sheer magnitude of migration stocks: about 232 million people lived outside their country of birth in 2013. Most migrants move across international borders to maximize their earnings and to gain opportunities, and most do make significant income gains. Whether these earnings gains are mirrored by improvements in reported well-being and broader quality of life is still largely an open question, however.

Higher levels of immigrant well-being can be instrumentally important for social outcomes such as public health and productivity, as happier individuals are typically more productive and healthier. In contrast, immigrant dissatisfaction may reflect lack of assimilation and social exclusion, and even extremist attitudes among natives, all of which can result in social unrest and lower economic output. From the point of view of the sending countries, meanwhile, emigrant well-being is important as migrants send remittances and contribute to the well-being of their home countries through investments, the spread of ideas, and technology.

Understanding the well-being consequences of migrating is challenging, as comparing migrants with those who did not migrate in either the sending or the destination countries is methodologically flawed. Such comparisons may simply reflect the traits of those who choose to migrate, and who may have differences in ability, risk tolerance, aspirations, and motivation, for example. The direction of causality between well-being and migration is also unclear: while migration may influence well-being, the reverse can also be true. While migration may indeed affect happiness, a recent paper using South American data finds that respondents who intend to migrate in the next year are wealthier and more educated than the average, but also less happy and more critical of their current and future economic opportunities.

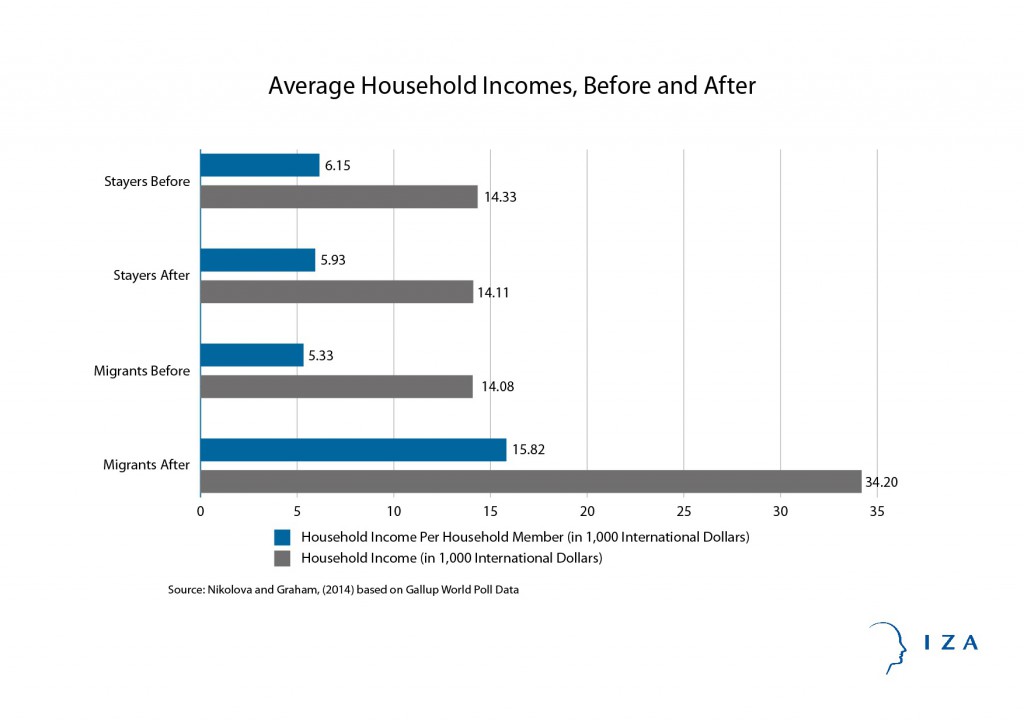

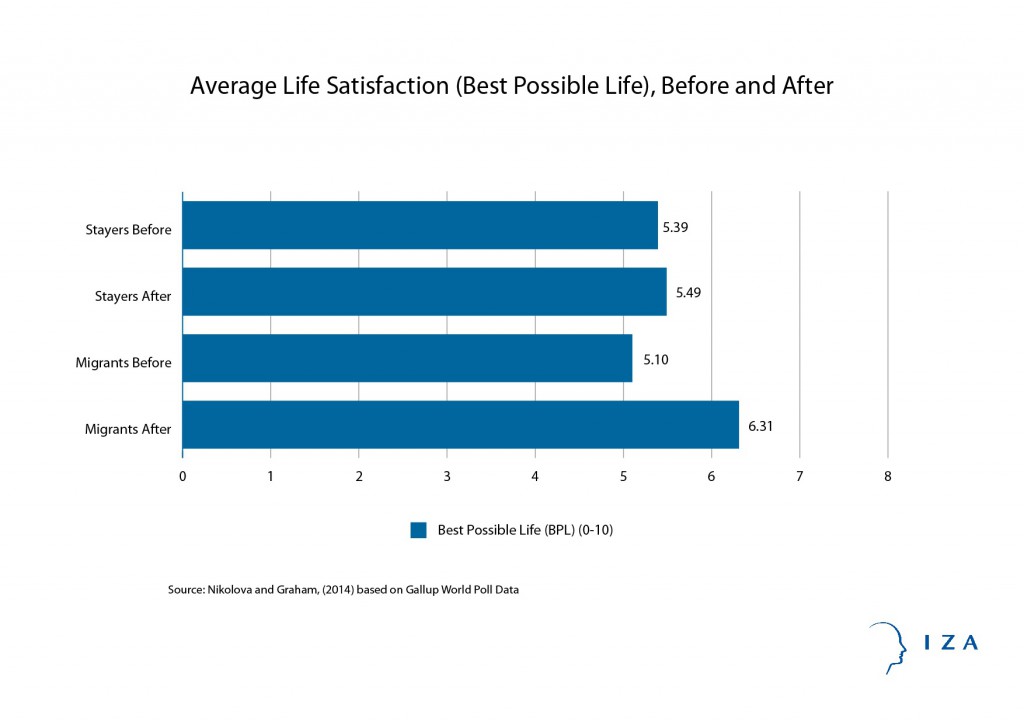

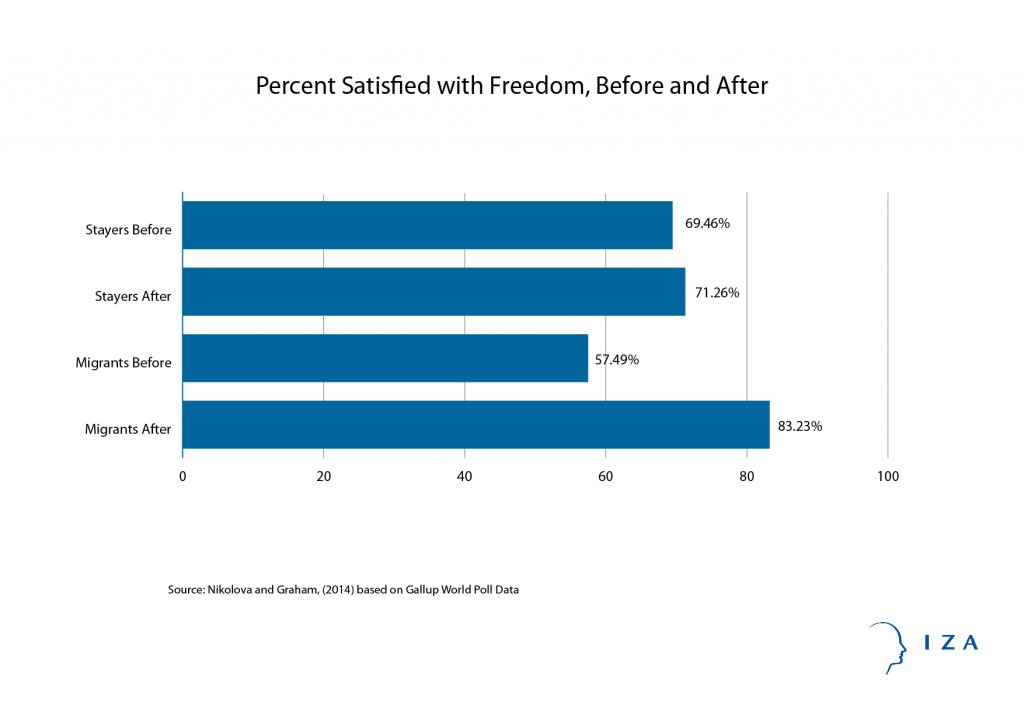

Despite the large income gains typically associated with migrating, it can also be accompanied by declining happiness because of adaptation and rising aspirations. While migrants’ (absolute) incomes increase, so do their expectations as they compare themselves to high-earning natives in the host countries. In a recent IZA Discussion Paper, we use Gallup World Poll data and statistical techniques to understand the well-being consequences of migration for movers from transition economies to advanced nations. Like other studies, we find unequivocal income increases due to migration. More importantly, we show that there are significant gains in life satisfaction and in perceptions of freedom. (See Figure 1 for the average well-being outcomes of migrants and stayers in the pre- and post-periods).

We studied migrants from transition and post-transition societies as they are quantitatively the most important migration source for the OECD economies in Europe. To illustrate, in 2012, Poland and Romania were among the top three migrant sources of OECD migrants. Migrants from transition economies leave countries, which are relatively more advanced and culturally similar to the destination countries, compared with movers from Asia, Africa, and Latin America, for example.

We find that migrants from transition countries achieve a better quality of life after they go abroad. The average household income premium from migration for our sample is about 21,000 international dollars (about 10,500 ID per household member). And even if reference norms and aspirations change, migrants’ life satisfaction also improves. The average benefit is substantively and statistically significant: an increase of about 1.0-1.2 (on a life satisfaction scale 0-10). Third, and perhaps most important, migration positively affects perceptions of freedom of choice, with migrants from the most recent EU enlargements being nearly 40 percent more satisfied with their freedom. Data from around the world show that freedom to seek life fulfillment is a pivotal element of human well-being.

At a time when there is ample reason to be concerned about the state of world affairs, our research findings are a “happy” story highlighting that by voting with their feet, migrants from transition economies can improve their well-being. Surely migration does not solve the problems in the countries the migrants left, nor can we be confident at this stage that our results apply to migrants from different origins and/or to those migrating to different destinations. Yet it does suggest that win-win outcomes are possible from increasing mobility in global labor markets. That is a story worth learning more about.

This post also appeared on the Brookings Institutions’s UP FRONT blog.

Milena Nikolova is a Research Associate at IZA and a Nonresident Fellow at Brookings. Carol Graham is the Leo Pasvolsky Senior Fellow at Brookings, College Park Professor at the University of Maryland, and a Research Fellow at IZA.