How did the labor market get through Covid-19 year 2020 in Europe? Broadly speaking, without much damage, according to a recent IZA Policy Paper by Stijn Baert (Ghent University). The percentage of unemployed among the 25 to 64-year-olds in the EU-27 rose 0.2 percentage points (pp) from 4.8% to 5.0%. By comparison, between 2009 and 2010, when the labor market digested the Financial Crisis of 2007–2008, this number increased by 1.3 pp at the EU-27 level.

This average obviously hides differences between EU countries. Most strikingly, in the Baltic states, the increase in percentage of unemployed is more than 1.5 percentage points and therefore substantial: Estonia (1.7 pp), Latvia (1.8 pp) and Lithuania (1.7 pp).

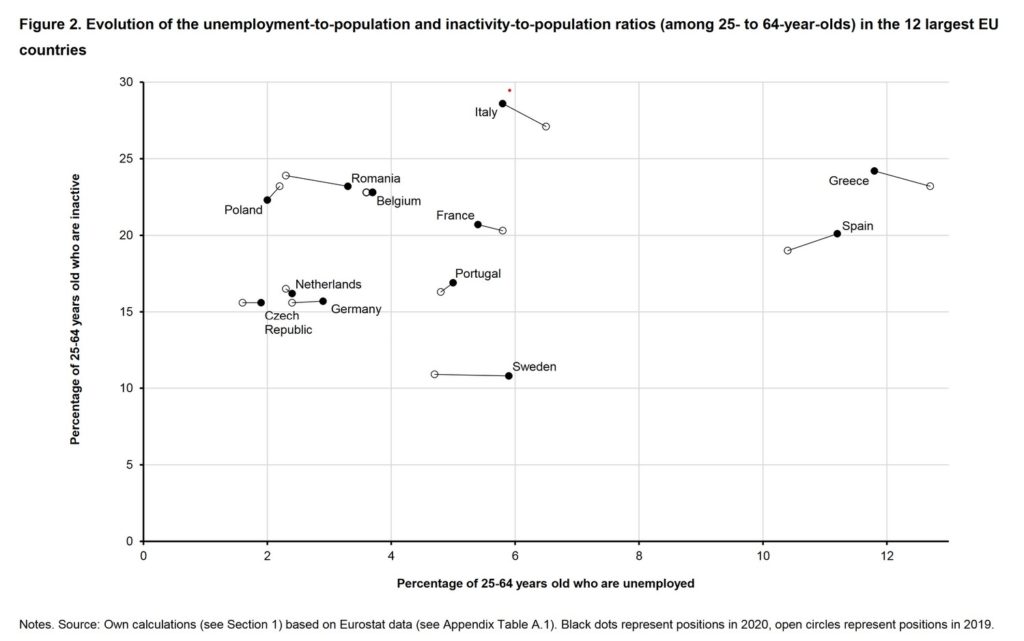

Among the other countries, only Romania (1.0 pp) and Sweden (1.2 pp) exhibit growth in their unemployment-to-population ratios in excess of 1 pp. Thereby, Sweden, often seen as a ‘model country’ even drops to 23rd place by unemployment (out of 27 countries).

Inactivity rose more sharply in Southern Europe

But what happened to the percentage of inactive people in 2020? While unemployed search for a job, this is not the case for inactive people. Did some of the unemployed become discouraged, partially masking the shift from employment to unemployment with a parallel shift from unemployment to inactivity?

Overall, the increase in inactive persons at the EU-27 level also remained rather limited. In 2019, 20.0% of the population was inactive; in 2020, that percentage rose to 20.3%—an increase of 0.3 pp. This rather small number still implies an increase by about 720,000 persons.

Again, we see important differences between countries. Inactivity rose more sharply in Southern Europe: Spain (1.1 pp), Italy (1.5 pp), Portugal (0.6 pp) and Greece (1.0 pp). Bulgaria (0.8 pp) and Ireland (0.8 pp) are also close to 1.0 pp increases in inactive persons.

Overall, the labor market of Poland experienced the most favorable evolution: despite the crisis, both the percentage of unemployed and inactive fell.

Germany’s position remains rather stable

Germany, the largest EU country by number of citizens, is not mentioned in the above discussion. This is because Germany remained fairly stable in terms of its position in the ranking of European countries.

Between 2019 and 2020, the percentage of unemployed among 25-64 year olds increased by 0.5 pp (i.e. from 2.4% to 2.9%). Admittedly a bit more than the European average, but because Hungary and Romania experienced a stronger increase, Germany rose from 7th to 5th place of best-performing countries in terms of unemployment.

The percentage of inactive persons rose even less, i.e. from 15.6% to 15.7%. This does mean, however, that Germany drops from 5th to 6th place as Latvia saw its inactivity percentage decrease despite Covid-19.

Overall, Germany is stable within the best quarter of European countries for both parameters.

What about 2021 and 2022?

Does the small overall effect of Covid-19 year 2020 mean that the ominous reports at the start of the crisis should be classified as misconceptions?

Stijn Baert:

“Not necessarily. The labor market almost always follows the pattern in economic growth at some distance. During the Financial Crisis, unemployment peaked about a year after the deepest decline in economic growth. If the current downturn in economic activity continues, it might not be possible to sustain the current level of labor hoarding, especially if support measures are removed. Much also depends on how the European countries deal with their accumulated debt: hard savings can be expected to deal an extra blow to the labor market, while well-considered investments could, through their multiplier effect, provide stimuli.”