As the world economy recovers from this year’s historic shock, millions of people will once again migrate each year from poorer nations to rich ones. Most come in search of work. Many richer countries seek to reduce the numbers of such migrants by encouraging economic development and opportunity overseas. “I want to use our aid budget [for] creating jobs in poorer countries so as to reduce the pressure for mass migration to Europe,” says British minister Priti Patel.

Will it work? When people in poorer countries get more economic opportunity, are they typically more likely to stay in their home countries? It may seem obvious. But two new IZA Discussion Papers reveal the opposite pattern: As people in poorer countries get richer, they are more likely to emigrate. In poor countries, sudden bursts of migration can be a sign of crisis. But sustained increases in migration are a sign of economic success.

The first paper, by Michael Clemens and Mariapia Mendola, studies this question at the level of households. Using data on 653,613 people in 99 developing countries, they find that people in households with higher income per adult are more and more likely to be making final, costly preparations to permanently emigrate.

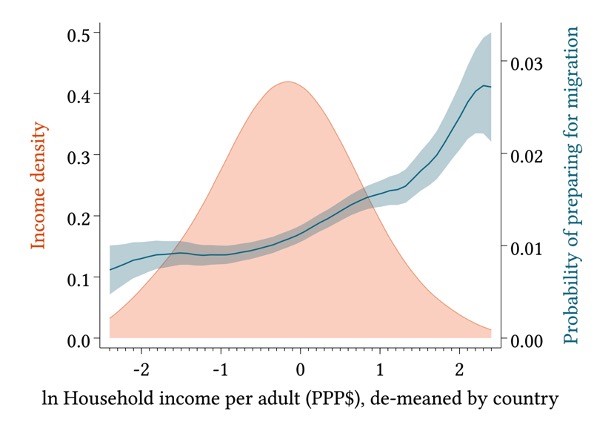

The figure below shows, in orange, the distribution of income for 120,420 people in the lowest-income countries of the world (left-hand axis). On top of that, in blue, is the probability that people at each income level are in the final stages of actively preparing to emigrate (right-hand axis).

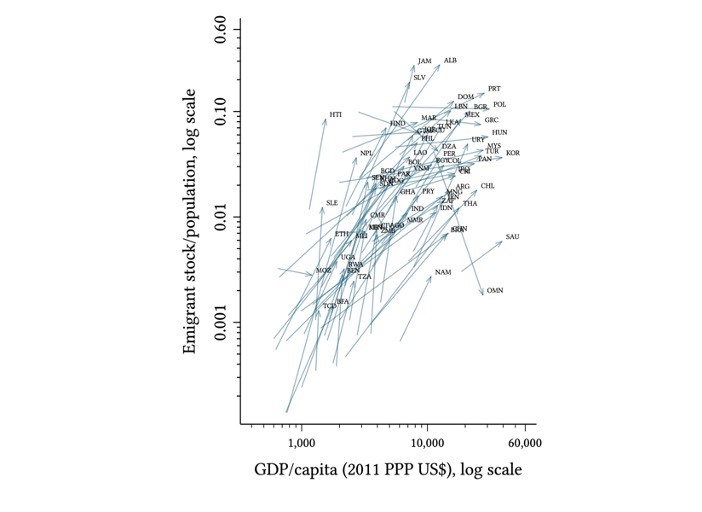

The second paper, by Michael Clemens, studies the same question at the level of nations. As poor countries get richer over time, larger fractions of their populations live outside them. The figure below shows emigration from poor countries to rich countries, on the vertical axis, and average income per capita on the horizontal axis. The arrows show how developing countries moved when they experienced economic growth between 1970 and 2019 (leaving out very small countries). Almost no developing countries have experienced sustained economic growth without a large rise in the emigrant fraction of the population.

These are only sketches of the results, on which the papers carry out numerous tests. For example, the first paper estimates positive self-selection—the greater migration tendency for people with higher earning power—on both observed determinants of earnings (like schooling) and unobserved determinants of earnings (like work ethic). It also checks whether emigration preparations reflect real emigration behavior. The second paper checks whether this pattern arises from differences in country traits that are fixed over time (like geographic location) or global changes that affect all countries (like improved transportation and communications technology).

The quantitative findings of the two papers, despite their different approaches, are strikingly similar. Across households within developing countries, a 100 percent rise in income per adult is associated with about a 30 percent increase in the propensity to be in the final stages of preparing to emigrate. Across developing nations, a 100 percent rise in average income per capita over time is associated with a 35 percent increase in emigration prevalence. In the very long term, economic development may substitute for migration, they find, but for the foreseeable future it is more likely to complement migration.

Why? Certainly it is not the case that workers prefer to stay in countries with less economic opportunity.

The easiest way to grasp the essence of this phenomenon, the authors write, is to think of migration as an investment in human capital. Moving to a new country, like investing in education, brings up-front costs with long-term benefits. Families with more money are more likely, not less likely, to send children to university even though they might have less ‘need’ for the income boost. The things that come along with higher incomes—more and better secondary schooling, and higher career aspirations, among others—produce higher university enrolment by richer families. Related forces are at work in migration. Economic development, too, brings changes of demography, schooling, urbanization, and other structural shifts that facilitate and inspire migration.

From a policy perspective, how should international development agencies engage with these facts? The authors caution against facile interpretation. The emigration of people from Africa is sometimes a sign of short-term crises, but it is simultaneously a sign of long-term economic success. Mass emigration from Scandinavia before 1914 was far from a sign of economic failure, but a sign of that region’s take-off into modern economic growth and the structural changes that came with it. Political debates that view development assistance as a migration deterrent—whether their arguments are pro-aid or anti-aid—may lack a basis in labor-market evidence.