Most economic research finds that the effect of the average immigrant worker on the average native worker is very small. There is much less agreement about the effect of the least-educated immigrant workers on the least-educated natives. Different studies reach conflicting conclusions, relying on a variety of strategies to separate mere correlation from true causes and effects.

This question is addressed with a nationwide policy experiment conducted by the United States government, in a new IZA Discussion Paper by Michael Clemens and Ethan Lewis.

Each year, firms in the United States apply to the federal government for permits to hire foreigners in temporary jobs that do not require a high school degree. About 100,000–130,000 such permits are given each year, across the country in industries including groundskeeping, hospitality, forestry, seafood processing, manufacturing, and construction.

Firms must enter a randomized lottery to pass a key step in the application process for these work visas. Using data on the lottery outcome and a new survey of firms, the study’s authors can observe what happens to groups of firms that can or cannot hire foreign labor for low-skill work, but otherwise start out identical.

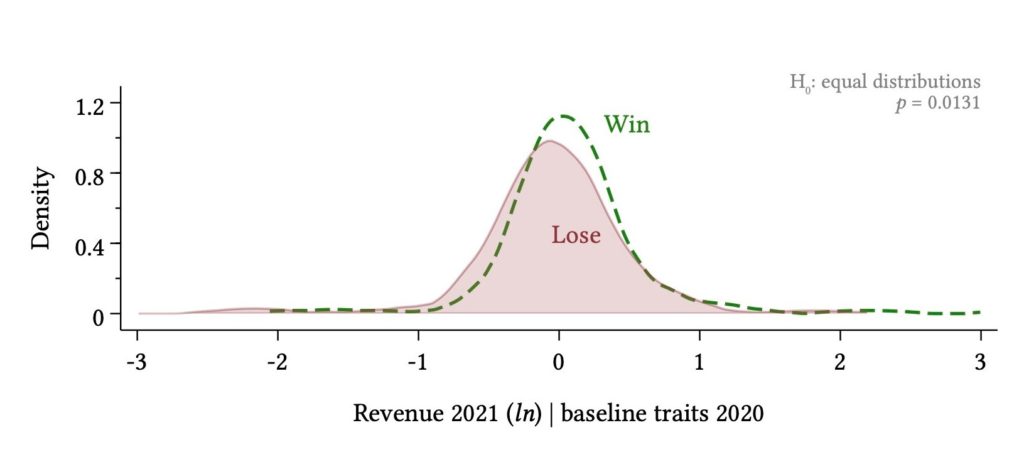

One key finding of the study is that firms contract when they are barred at random from hiring immigrants for low-skill work. When this force majeure obliges otherwise identical firms to reduce foreign hiring by 50 percent, they slash production by 9 percent. The graph below shows the distribution of output by firms that ‘win’ the lottery and can thus hire their desired number of foreign workers, as a dashed green curve. The distribution for firms that ‘lose’ the lottery, and are thus obliged to hire far fewer foreign workers, is the solid red curve.

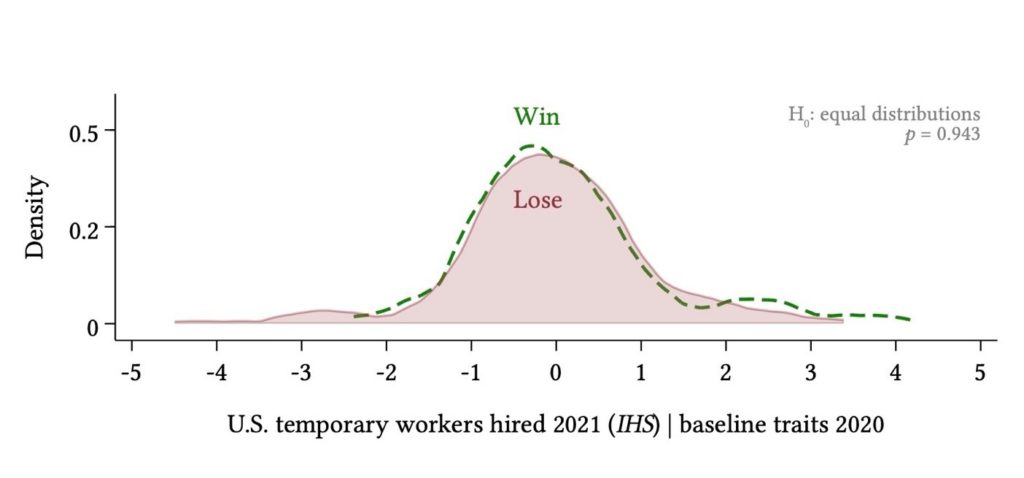

A second key finding is that firms barred at random from hiring foreigners for these jobs do not hire native workers as a replacement. The effect of losing the visa lottery on native hiring is not statistically distinguishable from zero, but if anything, losing the lottery results in fewer native hires. When otherwise identical firms are obliged to reduce foreign hiring for low-skill jobs by 50 percent, they reduce native hiring between zero and five percent.

In the graph below, the distribution of native hiring among ‘winning’ firms is the dashed green line. The distribution of native hiring among ‘losing’ firms is the solid red line. There is a high probability that any differences between these distributions arise only from chance.

These results have relevance to U.S. immigration policy because they study the impact of policy change: access to the country’s principal work visa for low-skill jobs. The results imply that for the policy-relevant occupations, native workers are extremely poor substitutes for native workers. The results cannot be interpreted as quantifying the overall effect of immigration for low-skill jobs on national GDP, however, because only effects at individual firms are directly measured.