Pay-for-performance compensation schemes are used across a wide range of industries and occupations. Even contracts that offer a fixed salary may be implicitly tied to performance by promotion and termination incentives.

Firms offer performance-based pay to motivate workers to supply costly effort, but they may accomplish more than simply inducing employees to work harder in applying their existing skill set. Indeed, such contracts may also induce workers to acquire new skills that make them better at their job, a much more desirable outcome from the firm’s perspective.

In a recent IZA discussion paper, Joshua Graff Zivin, Lisa B. Kahn and Matthew Neidell provide the first empirical evidence on the impacts of performance-based compensation schemes, and particularly the use of bonus payments, for on-the-job learning.

Evidence from grape and blueberry farms

The researchers analyzed data from a grape and blueberry farm that utilizes two distinct contracts to compensate workers for their efforts. Fruit picking provides an ideal setting to evaluate the effects of incentive schemes because workers’ individual productivity can be measured precisely.

The contract for grape pickers paid a fixed wage up to a productivity target and a piece rate thereafter. The contract for blueberry pickers paid a fixed wage up to a productivity target, a bonus for reaching the target, and a piece rate thereafter. The focus of the study was on whether the stronger incentives embedded in the second contract, the one for the blueberry pickers, translated into more or faster learning on the job.

Bonus payment led to faster learning

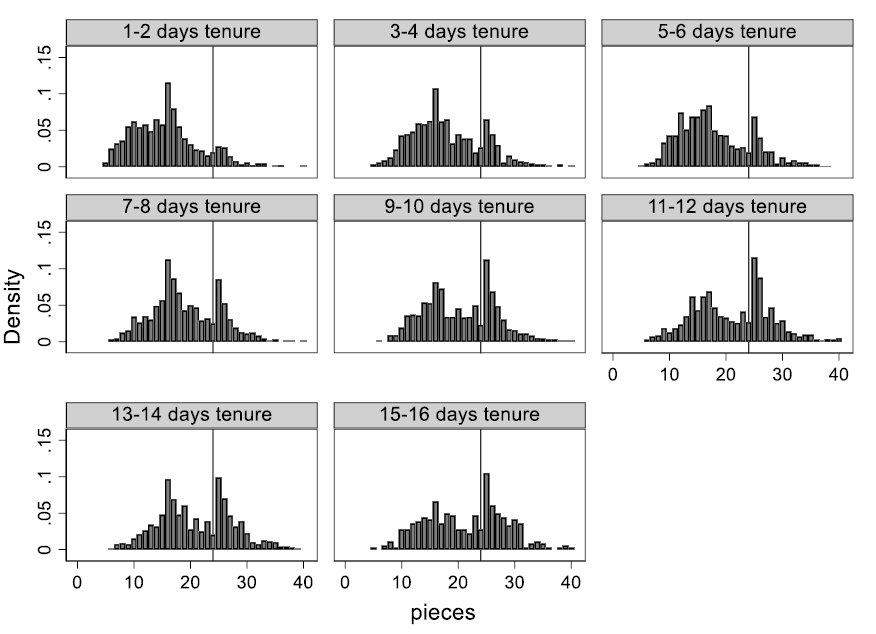

Consistent with the literatures on salespeople and executive compensation, the authors find that the contract that included a bonus led to “strategic heaping” around the threshold: workers raise their productivity just enough to qualify for the bonus. Importantly, heaping becomes more likely as workers gain more experience and are better able to reach the threshold (see Figure 1).

For workers under the commission-only contract (the grape pickers), such heaping or changes in heaping were not observed (see Figure 2). While blueberry pickers increased their likelihood of hitting the piece rate threshold by 15 percentage points (80%) over their first 10 days on the farm, grape pickers saw very little improvement.

Costly bonus contracts pay off for the employer

In essence, the contracts with bonuses tied to productivity targets generate faster learning-by-doing than those induced by a simple commission scheme. Moreover, these productivity improvements were not simply limited to those close to the bonus threshold. Instead, learning occurred throughout the productivity distribution.

Overall gains in productivity from those well below the bonus threshold more than offset the costly bonus payments: A simple back of the envelope calculation based on empirical estimates of learning-by-doing under the blueberry contract suggests that the learning induced from day 3 to day 10 of tenure generates an additional $60 in net revenue per worker, or approximately $8.50 per day.

Compensation schemes designed to incentivize effort thus also play an important role in learning and skill acquisition by workers. According to the authors, this suggests such incentives may be an important tool to improve firm productivity also in different settings.