What are the historical drivers of happiness? To answer this question, a research team from the University of Warwick built an index of subjective well-being for the last 250 years, based on sentiment analysis of millions of digitized books.

What are the historical drivers of happiness? To answer this question, a research team from the University of Warwick built an index of subjective well-being for the last 250 years, based on sentiment analysis of millions of digitized books.

By Thomas Hills, Eugenio Proto and Daniel Sgroi

Aiming at national accounts of subjective happiness instead or in addition to traditional measures of economic growth has been promoted by many different actors, like the UN World Happiness Report, the OECD’s Better Life Index, among a number of economists and politicians. While there is a general consensus to better understand subjective well-being and happiness, subjective well-being is a rather young indicator, the systematic measurement of national happiness has only begun in the 1970s.

More traditional indicators of economic well-being like the national accounting of the gross domestic product (GDP) started off in the 1930s, with successful projects to roll back GDP even further, such as the Madison Historical GDP Project. No such attempt has been undertaken so far for national happiness. Still, knowing about greater historical trends in happiness would allow us to better understand how well-being responds to key historic events, such as expansionary monetary policies, education, and longevity.

Going back in time, thanks to digitization

How can we extend existing subjective well-being measures when direct survey evidence was only initiated in the 1970s? We argue that language conveys sentiment, and that the growing availability of digitized text provides unprecedented resources to construct a quantitative history of well-being based on historical language use. We combine multiple large corpora of natural language going back two centuries with state-of-the-art methods for deriving public mood (i.e., sentiment) from language.

The recent large-scale digitization of books, newspapers, and other sources of natural language represent historically unprecedented amounts of data on what people thought and wrote over the past few centuries. These databases have already proved fruitful in detecting large-scale changes in language, which in turn correlate with social and demographic change.

These data offer the capacity to infer public mood using so-called sentiment analysis. Deriving sentiment from large collections of written text represents a growing scientific endeavor. Examples include recovering large-scale opinions about political candidates, predicting stock market trends, understanding diurnal and seasonal mood variation, detecting the social spread of collective emotions, and understanding the impact of events with the potential for large-scale societal impact such as celebrity deaths, earthquakes, and economic bailouts. Applying the same methods to historical text, we can begin to produce more quantitative accounts of national happiness.

Word usage shows how people feel

The approach is based on valence norms, large-scale survey-based ratings of how certain words make people feel. In the present case, valence norms based on the Affective Norms for English Words have already been collected for five languages: English, French, Spanish, Italian, and German. We combine these valence norms with frequencies of these words extracted from the large historical database of Google Books to derive proxies for subjective well-being going back to 1776.

An initial comparison with survey-based subjective well-being is shown in the figure on the right. Accounting for potential time-invariant differences in happiness, the measure based on historic language and the self-reported measures are closely related.

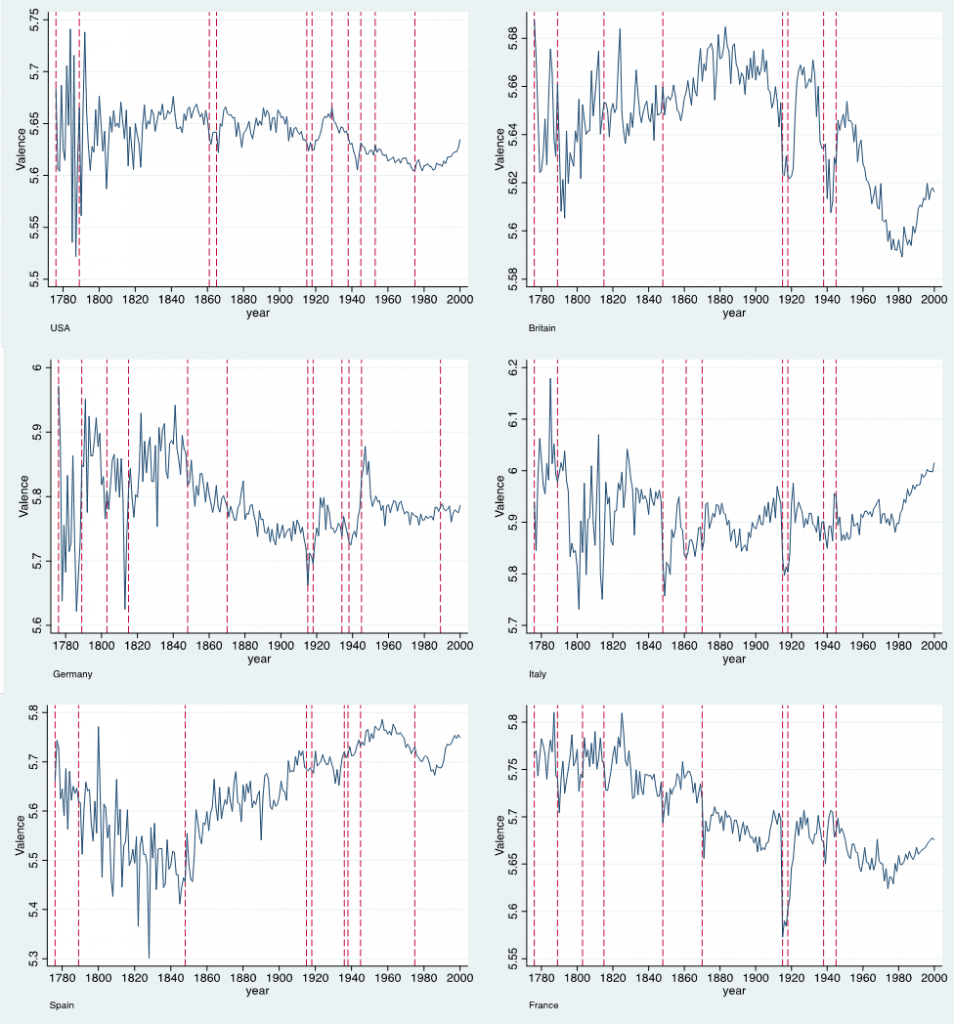

Based on this observation for periods where both language-based and subjective measures exist, we roll back the text-derived measures of subjective well-being back to 1776. This reveals a quantitative picture of how public sentiment has historically changed across the six countries.

How conflicts and other historic events affect subjective well-being

The figure below displays the reaction of this historical measure of well-being on short-term events, such as the exuberance of the 1920s, the depression era, and World War I and II show clear and distinguishable influences on subjective well-being. Sharp declines follow internal and external conflicts, recessions and political turmoil.

For all countries the vertical red lines correspond to 1789, the year of the French Revolution, to World War I (1915-18) and to World War II (1938-45). In the five European countries a line is drawn in 1848, the year of the revolutions. Moreover, in the US, the vertical lines represent: the Civil War (1861-65), the Wall Street Crash (1929), the end of Korean War (1953) and the fall of Saigon (1975). In the UK, the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15). In Spain, the starting of Civil War (1936). In France, the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15), the end of the Franco-Prussian War (1870). For Germany, the vertical lines represent the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15), the Franco-Prussian War and unification (1870), Hitler’s ascendency to power (1934), the reunification (1990). In Italy, the unification (1861-70).

Why is a quantitative history of well-being important?

The fledgling state of well-being data has limited the collective ability to understand how subjective well-being responds to different historic events. This has in turn limited the use of subjective well-being as a target for public policy, health initiatives, and financial decision making. In practice, if subjective well-being is to become a key factor in guiding collective behavior, then we need accounts of well-being on par with those of GDP.

Using well-being as a measure to guide behavior, however, takes more than the desire to simply improve well-being. As noted by Daniel Gilbert in Stumbling on Happiness, people have problems understanding what is called affective forecasting—the ability to understand how one will feel in the future—and with this also comes a limited capacity to understand how prior events and decisions influenced our past happiness.

To overcome this, especially at the level of government, we must develop our capacity to predict how well-being responds to both deliberate and unexpected events. Better predicting economic fortunes was the motivation of the national income accounting following the depression in the 1930s, which later became the GDP. Of course, now numerous decisions are based on the GDP, despite a near global acceptance that, in the words of Robert F. Kennedy, “it measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile”.

Thus, like GDP, governments and other agencies recognize the importance of this additional ‘emotional accounting’ and, by all accounts, they want to understand how better to use it to improve future well-being. But to do that, we need historically informed accounts of what this means.