With already over half a million deaths globally, the COVID-19 crisis has distracted public attention from pressing environmental issues such as climate change and pollution. Yet, there is a striking connection between the health effects of the pandemic and air pollution, according to a new IZA discussion paper by Ingo E. Isphording and Nico Pestel.

The study shows that higher levels of local air pollution increase the number of deaths related to COVID-19. One of the reasons is that air pollution leads to inflammatory reactions and lower immune responses to new infections, which exacerbates the course of the illness. In addition, some studies have argued that higher levels of air pollution prolong the time the virus remains in open air, thus increasing the number of infections.

The authors link pollution patterns, measured by particulate matter (PM10), surrounding the day of onset of illnesses to the numbers of deaths and newly confirmed cases of COVID-19 in German counties between early February and late May. By focusing on changes in air pollution within counties rather than cross-sectional correlation between countries in death numbers and pollution, the estimated relationship can be interpreted as a causal effect of air pollution levels on the number of deaths.

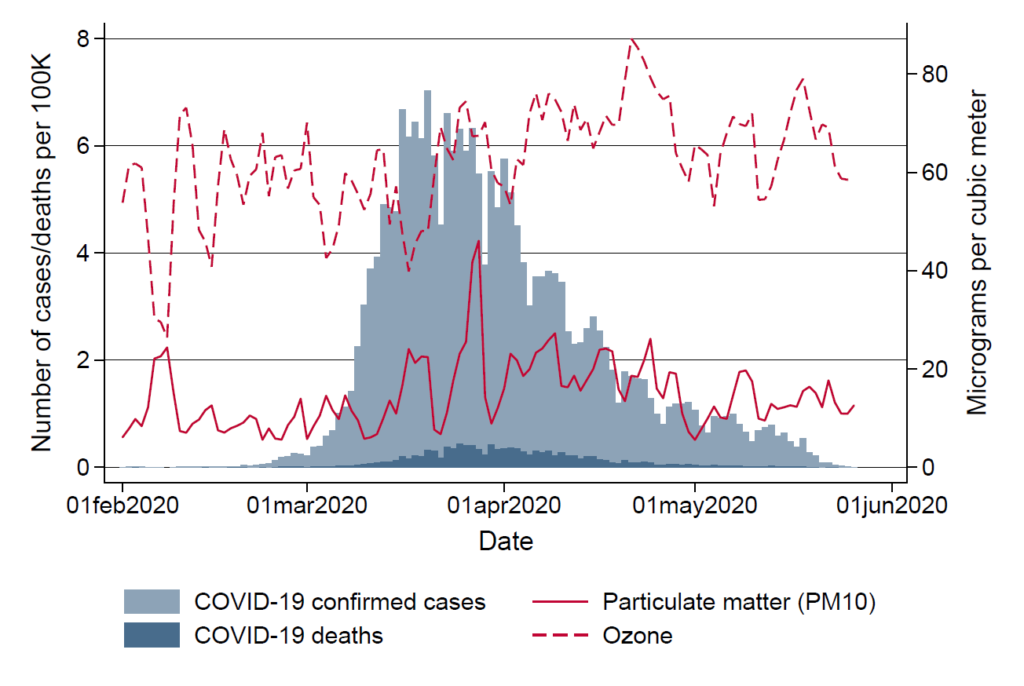

Figure 1: Daily variation in new con firmed cases and deaths and mean air pollution

Figure 1 describes the level of pollution across the course of the pandemic in Germany. In contrast to the common perception that air pollution decreased during the lockdown due to lower traffic and economic output, the data shows that air pollution levels actually remained high and even peaked in late March. This can mainly be attributed to weather conditions as the lockdown in Germany happened to coincide with a sudden drop in precipitation and wind speed, which made particulate matter stay in the air longer.

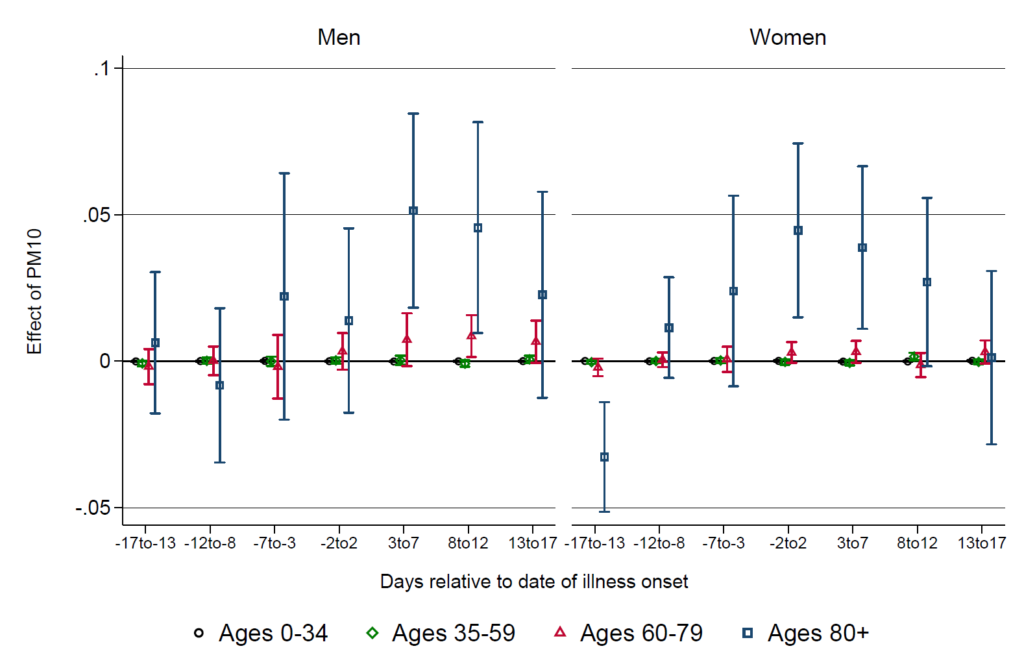

The regression results show significant effects of higher air pollution on the number of deaths by day and county (Figure 2). Effects are specifically pronounced for patients aged 80 and above. In this age group, a one standard deviation increase in PM10 (6.3 microgram/m3) three to seven days after the onset of illness increases the number of deaths among male patients by 30 percent of the baseline mean, with comparable effects for female patients.

Figure 2: E ffect of PM10 on new deaths from COVID-19

These results imply that moving older patients, who are at higher risk of dying of COVID-19 when being exposed to higher levels of air pollution, to less polluted areas might be a way to reduce the case fatality rate of COVID-19. This could be of particular relevance when the pandemic unfolds in less-developed world regions where air pollution and associated health risks are stronger, e.g., through the more widespread (indoor) use of fossil fuels for cooking and heating, and where supply of high-quality medical care is constrained.