Scientific research confirms the influence of attractiveness on job prospects. While previous studies mainly examined factors beyond personal control, such as physical beauty and obesity, a new IZA discussion paper focuses on the importance of another external characteristic: body art, namely piercings and tattoos. How does visible body art affect job opportunities, and what perceptions do employers hold regarding candidates with body art?

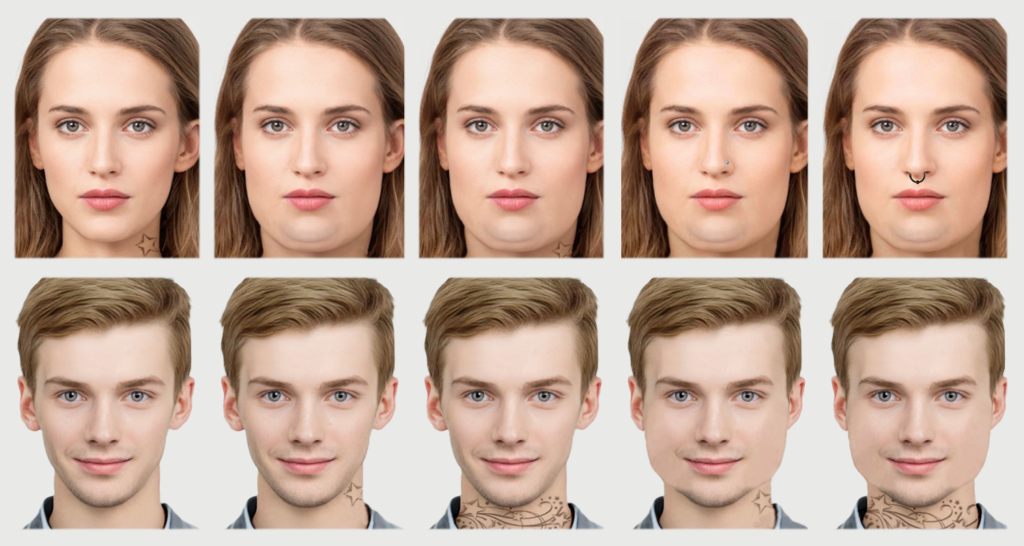

To address these questions, Stijn Baert, Philippe Sterkens and Jolien Herregods conducted a large-scale experiment involving U.S. recruiters. They asked the recruiters to evaluate fictitious job candidates whose AI-generated photos varied in whether they had visible small or large tattoos or piercings. Additionally, the photos (see examples below) were manipulated to compare the effect of body art with another aspect of physical appearance – obesity.

Recruiters were not only tasked with advising colleagues on whether to invite the candidates for job interviews but also to identify any potential stigmas associated with body art, including eagerness to work with such candidates, personality traits, and productivity drivers.

Differences in perceived personality traits and productivity

The findings revealed that recruiters perceive job candidates with body art as less pleasant to collaborate with, both in terms of recruiters’ personal preferences for collaboration and their perceptions of other employees’ and clients’ preferences for collaboration. Regarding personality, candidates with body art are seen as less honest, less emotionally stable, less agreeable, and less conscientious overall. Notably, the stigma of lower emotional stability only applies to men with body art. On the other hand, job candidates with body art are also seen as more extroverted and open to new experiences. However, in terms of direct productivity drivers, they are perceived as less manageable.

These perceptions ultimately result in lower hireability for men with body art but not for women. Compared to candidates who are obese, those with body art score better overall in terms of hireability and rated personality, and similarly in terms of rated taste for collaboration, but worse in terms of rated direct productivity drivers.

Considering these findings, body art wearers (and overweight individuals) and those assisting them in the labor market, such as public employment agency officers, should be mindful of the stigmas they may encounter when applying for jobs and the contexts in which they might face higher thresholds for success.

The authors suggest that individuals with body art would benefit from signaling qualities like honesty, stability, and conscientiousness during job applications. For instance, examples of conscientiousness, a personality trait found to be highly valued by employers, could be highlighted in the cover letter.