Early childhood years are highly formative and often provide the basis for educational, professional and social achievements in adulthood. IZA World of Labor features two recent articles which examine early childhood conditions and their policy implications from different angles: preschool programs and public health interventions.

Early childhood years are highly formative and often provide the basis for educational, professional and social achievements in adulthood. IZA World of Labor features two recent articles which examine early childhood conditions and their policy implications from different angles: preschool programs and public health interventions.

Already at the age of six, children show differences in their educational development. Kids from low socio-economic status families, many with an immigration background, are often unprepared to enter primary school and run the risk of falling behind. Existing research has shown for some time now that small model preschool programs can lead to substantial improvements in school readiness for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, who would otherwise have little access to high-quality early childhood care or education. This initial evidence confirmed on a small scale that preschool can be an effective way to reduce inequality. But the question has always been whether universal programs provided at scale could also deliver on that promise.

Preschools strongly reduce inequality in child development

As Jane Waldfogel (Columbia University) shows in her IZA World of Labor article, the answer is yes. Publicly provided preschools can strongly reduce such inequality in child development and yield long term positive effects for disadvantaged children. Recent studies show that adults who come from disadvantaged backgrounds and profited from preschool programs in the 1970s and 1980s, have achieved better academic results and underwent a more stable social and emotional development than those without preschools. Assessments from newer universal preschool programs in several US states and cities point in the same direction and complement the evidence on the long-term effectiveness of large scale universal preschool programs.

But for such programs to be effective, policy makers must coordinate with school policies and provide adequate funding. Waldfogel stresses that effective preschool programs require highly educated and trained preschool staff, reasonable class sizes and low teacher–student ratios. She underlines that investment in such conditions pays for itself, because especially for countries where inequality is high and persistent, such as the US, they both raise students’ overall achievement and reduce social inequality.

Moreover, there needs to be complementarity and coordination between preschool and school policies. If children receive a better and more equal education in preschool, the material that is taught in kindergarten and primary school should build on that knowledge. Finally, Waldfogel calls for broader policy coordination and recommends that other policies, such as those aiming at parenting and income support, buttress preschool efforts.

Public health interventions for children have long-term positive effects

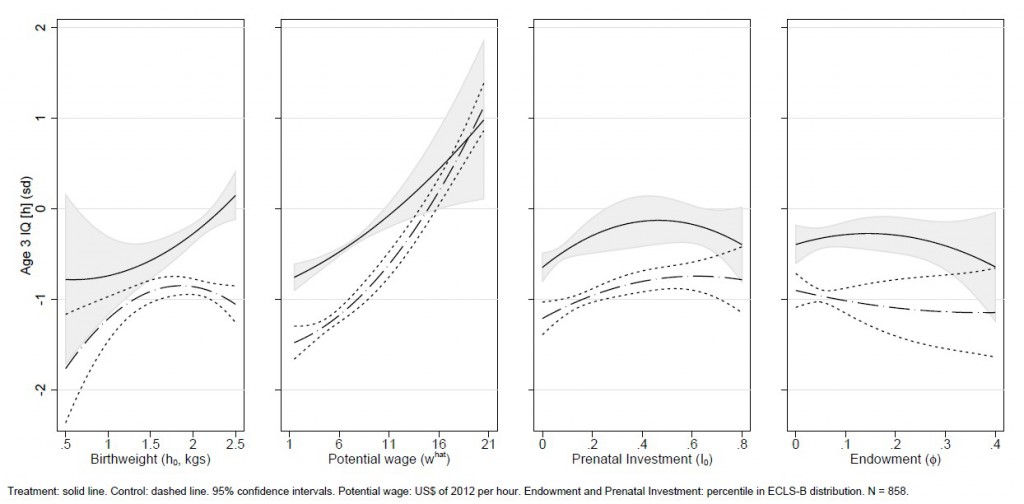

The IZA World of Labor article by N. Meltem Daysal (University of Southern Denmark) maintains that investments in early childhood conditions should not only target education, but also health. A large body of empirical research shows that adverse health conditions during early childhood have long-term negative implications. If young children experience circumstances such as poor nutrition, illness, in-utero alcohol exposure, iodine deficiency or psychological stress it is likely to negatively affect not only adult health, but human capital accumulation and economic outcomes during adulthood, too.

For example, an analysis of OECD data revealed a negative correlation between low birth weight and average years of schooling (see graph). In her article, Daysal investigated if early-life medical care and public health interventions are able to ameliorate these effects. Reviewing current research, she finds that both types of interventions may benefit overall child health, reduce child mortality and improve long-term educational outcomes. Special programs designed to eradicate certain child diseases or aiming at educating mothers about child nutrition have shown to raise both health and educational conditions such as school enrollment, attendance, and literacy rates.

However, Daysal emphasizes that not all interventions are universally beneficial. While the evidence is convincing for at-risk children, she found only mixed results with regard to the impact on low-risk children. Thus policymakers should carefully consider potential differences in responses to public health programs across population groups and design public health interventions for those who need it most, such as low-educated or low-income parents. Daysal notes that some medical interventions benefit not only the treated children, but also their siblings. These spillovers should be taken into account when designing policies aimed at improving early childhood health.

Featuring high-quality international research on related issues, IZA is holding a workshop on “Education, Interventions and Experiments” this week.

Income inequality levels and trends are increasingly a subject of public discussion and have been analyzed in depth by economists and other social scientists. Major books about inequality receive wide attention, such as Tony Atkinson’s

Income inequality levels and trends are increasingly a subject of public discussion and have been analyzed in depth by economists and other social scientists. Major books about inequality receive wide attention, such as Tony Atkinson’s  Electronic self-service platforms can help job-seekers find suitable vacancies and facilitate self-development. But the results of a recent research project by

Electronic self-service platforms can help job-seekers find suitable vacancies and facilitate self-development. But the results of a recent research project by  A large empirical literature supports the view that linking payment to performance is highly effective in raising productivity. However, often little attention is paid to how performance incentives are implemented in employment contracts. While most employers work with bonuses, some also arrange penalty contracts that set a base wage, part of which can be lost if performance targets are not reached.

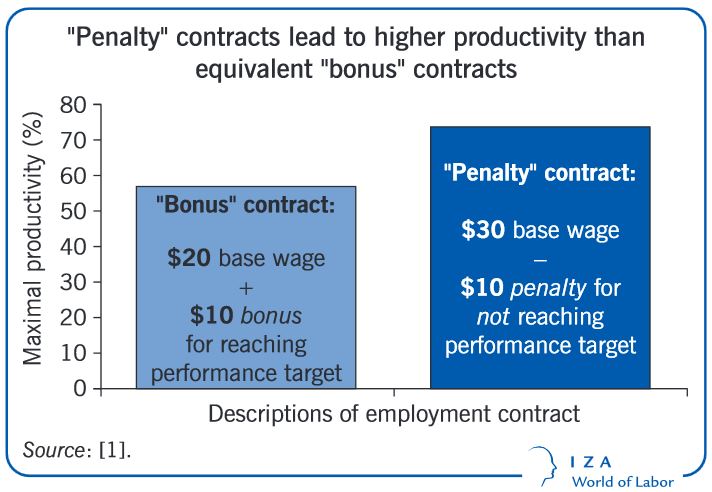

A large empirical literature supports the view that linking payment to performance is highly effective in raising productivity. However, often little attention is paid to how performance incentives are implemented in employment contracts. While most employers work with bonuses, some also arrange penalty contracts that set a base wage, part of which can be lost if performance targets are not reached.

The standard empirical evaluations of labor market policy only consider the direct effects of single programs on their participants. This column* (based on

The standard empirical evaluations of labor market policy only consider the direct effects of single programs on their participants. This column* (based on  Notes: Effects are expressed in percent of average monthly earnings within 3.5 years after unemployment (3547 CHF = 3290 EUR = 3575 USD in sample). Treatment effects: effects of being exposed to at least one carrot (job search assistance, training) or stick (sanction, workfare program). Regime effects: marginal effect of changing policy intensity by 0.1.

Notes: Effects are expressed in percent of average monthly earnings within 3.5 years after unemployment (3547 CHF = 3290 EUR = 3575 USD in sample). Treatment effects: effects of being exposed to at least one carrot (job search assistance, training) or stick (sanction, workfare program). Regime effects: marginal effect of changing policy intensity by 0.1. Notes: Marginal effects of changing the regimes by 0.5 standard deviation (i.e., about 0.1 in policy intensity). Earnings changes: in percent of average monthly earnings of non-treated individuals. Cost changes: in percent of total benefit cost per person.

Notes: Marginal effects of changing the regimes by 0.5 standard deviation (i.e., about 0.1 in policy intensity). Earnings changes: in percent of average monthly earnings of non-treated individuals. Cost changes: in percent of total benefit cost per person. What many have already suspected has now been scientifically proven: Employers are screening job candidates through Facebook. In fact, your Facebook profile picture affects your callback chances about as strongly as the picture on your resume. This is the finding of a

What many have already suspected has now been scientifically proven: Employers are screening job candidates through Facebook. In fact, your Facebook profile picture affects your callback chances about as strongly as the picture on your resume. This is the finding of a  The study by

The study by  Environmental policy pertaining to air pollution has been estimated to have large health benefits. However, these policies also come with costs. Production is typically reallocated away from newly regulated industries to other sectors and locations, and this creates a broad set of private and social costs. In terms of labor inputs, this reallocation is often framed in terms of “jobs lost,” and the distinction between “jobs versus the environment” is one of the more politically salient aspects of these regulations.

Environmental policy pertaining to air pollution has been estimated to have large health benefits. However, these policies also come with costs. Production is typically reallocated away from newly regulated industries to other sectors and locations, and this creates a broad set of private and social costs. In terms of labor inputs, this reallocation is often framed in terms of “jobs lost,” and the distinction between “jobs versus the environment” is one of the more politically salient aspects of these regulations. Human development starts early, and neuroscientists point to the first three years of brain development as especially consequential. Foundations for academic and social success later in life are created through the experiences in children’s earliest years.

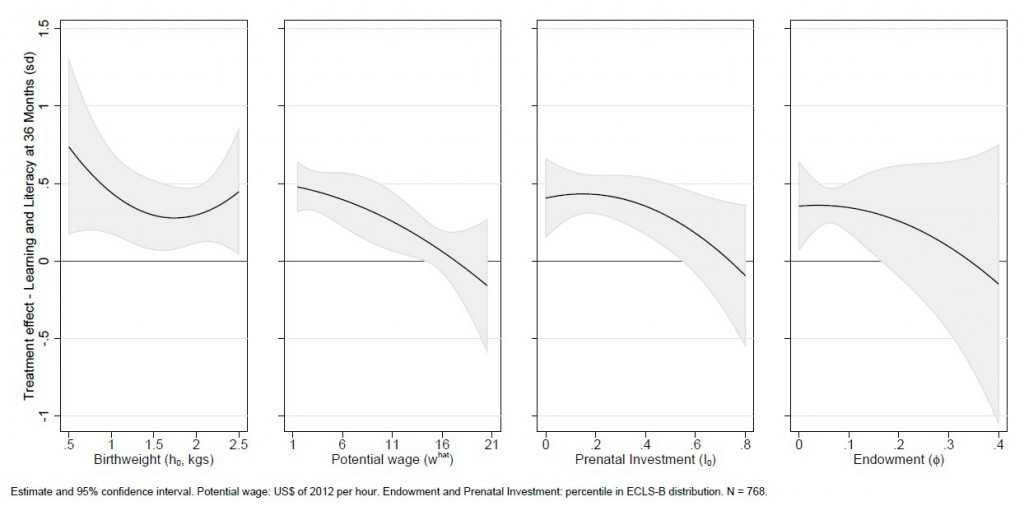

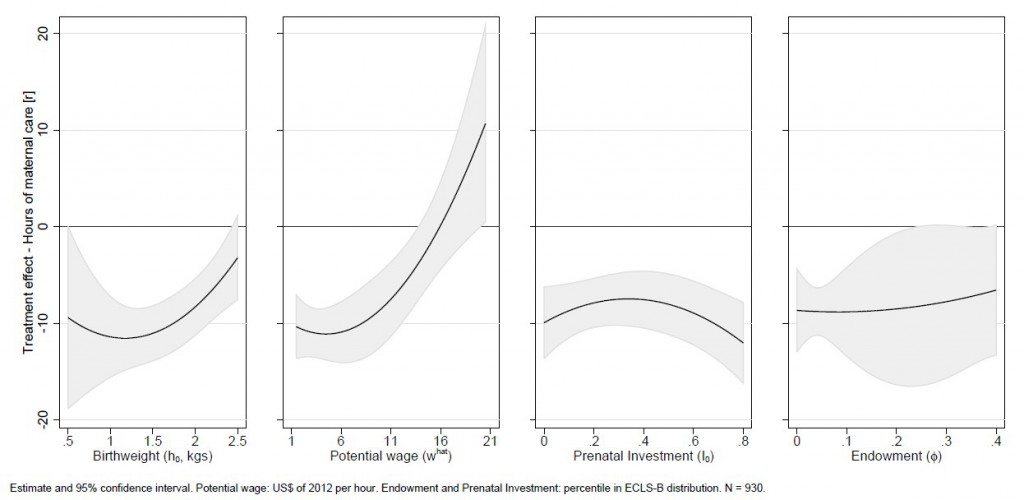

Human development starts early, and neuroscientists point to the first three years of brain development as especially consequential. Foundations for academic and social success later in life are created through the experiences in children’s earliest years.

increasingly cognizant of the long-term consequences of student absenteeism and suspensions, which are particularly troubling given that absence and suspension rates are significantly higher among low-income and racial minority students. However, while credible evidence of the harm caused by primary school absenteeism

increasingly cognizant of the long-term consequences of student absenteeism and suspensions, which are particularly troubling given that absence and suspension rates are significantly higher among low-income and racial minority students. However, while credible evidence of the harm caused by primary school absenteeism  integration and digital communication are undoubtedly bringing people closer together. But do they also cause the levels of satisfaction to converge? Researchers have long studied the institutional factors contributing to the strong international differences in life satisfaction.

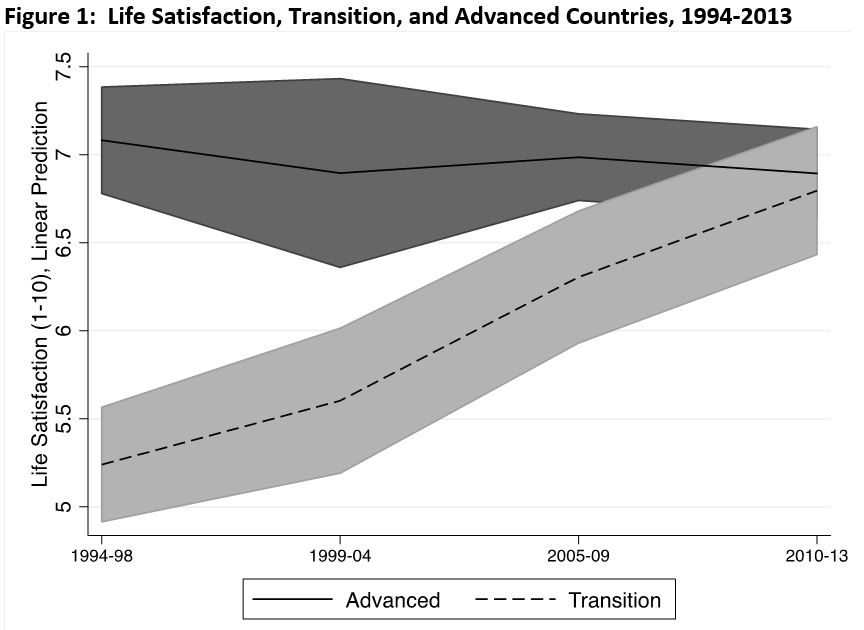

integration and digital communication are undoubtedly bringing people closer together. But do they also cause the levels of satisfaction to converge? Researchers have long studied the institutional factors contributing to the strong international differences in life satisfaction.