Concerns about loneliness are growing more than ever. Population ageing, the rising number of people living alone, global mobility, changes in working methods and the increased use of digital technologies for communication have led many to suggest that loneliness is becoming more prevalent. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns, quarantines, curfews, distancing measures, the cancellation of community activities and events have magnified existing levels of loneliness and social isolation. With the pandemic entering its second year, there are fears that the toll on loneliness could have consequences long after the virus recedes.

The impact of loneliness on individual well-being and social cohesion should not be underestimated. Loneliness has been compared to obesity and smoking in the mortality risks that it entails. It is also associated with physical and psychological health problems. Lonely adults tend to suffer from higher levels of cortisol (the ‘stress hormone’), raised blood pressure, impaired sleep and cardiovascular resistance compared with non-lonely individuals, both in stressful situations and when at rest.

Over time, this translates into chronic inflammation and higher morbidity and mortality rates. Loneliness is also associated with depressive symptoms and with unhealthy behaviors such as smoking and a lack of physical exercise. In an increasingly connected world, lonely and socially isolated people face the double penalty of poorer health and being stigmatized as socially awkward.

Behavioral effects of loneliness create a vicious circle

What is more, feelings of loneliness and social isolation may themselves drive lonely individuals even further away from others, because loneliness affects behavior. Individuals suffering from loneliness and social isolation tend to display lower levels of empathy and feel more threatened by unexpected life situations compared with their non-lonely counterparts.

Although discussions about loneliness are prominent in political debates, and a growing number of newspapers are now talking about a ‘loneliness pandemic’, cross-national evidence on the incidence of loneliness is still limited. A recent IZA discussion paper by Béatrice d’Hombres, Martina Barjaková, and Sylke V. Schnepf offers a comparative overview of the prevalence and determinants of loneliness and social isolation in Europe in the pre-COVID period.

One-fifth of the European population suffers from social isolation

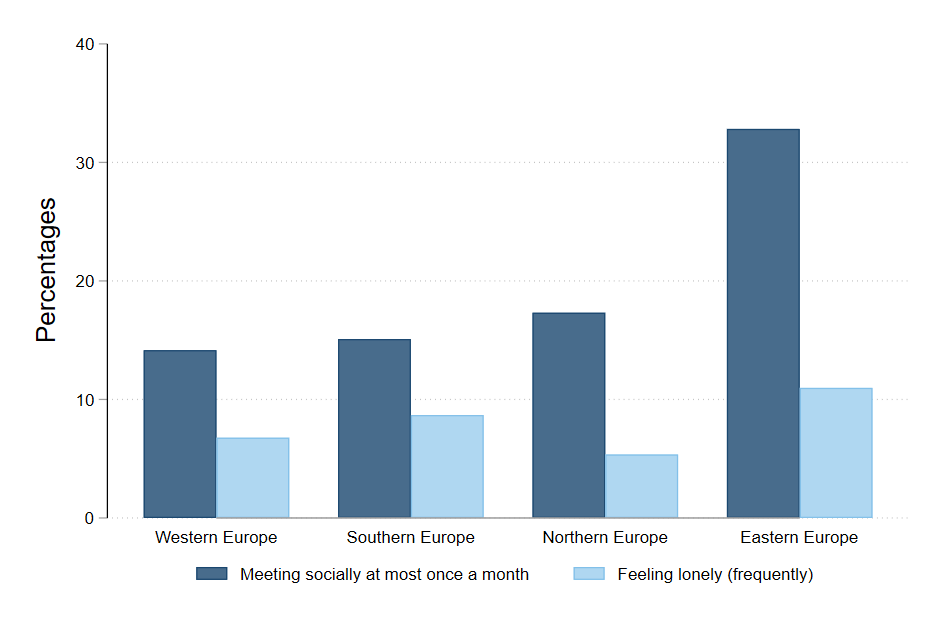

The empirical results indicate that 8.6% of the adult population in Europe suffer from frequent loneliness and 20.8% from social isolation, with eastern Europe recording the highest prevalence of both phenomena. Trends over time do not indicate any change in the incidence of social isolation following the widespread adoption of social media networks from 2010 onwards. The empirical analysis shows that favorable economic circumstances protect against loneliness and social isolation, while living alone and poor health constitute important loneliness risk factors.

Figure: Prevalence of Loneliness and Social Isolation in EU macro regions

Although social isolation increases with age, the elderly do not report more frequent feelings of loneliness than other age groups, all other things being equal. The authors show that the relative contributions of the different objective circumstances included in the empirical analysis — demographic characteristics, economic conditions, living arrangements, health status, religious beliefs and geographical location — to loneliness and social isolation vary substantially.

Forced social distancing may have long-term consequences

Data limitations precluded an investigation of the role of social media in protecting against or increasing the risk of social isolation and loneliness. The authors suggest this should be addressed in future pan-European studies on loneliness. Future research should also examine whether loneliness influences civic behavior and, more broadly, attitudes towards others and general trust, two important components in the functioning of liberal democracies.

Social connections are critical in our daily lives. The distress experienced worldwide over the past year is, in part, driven by limitations on social interactions. The forced social distancing experienced since March 2020 and the economic effects of the pandemic are likely to have long-term consequences. A forthcoming study will evaluate the extent to which the current situation has exacerbated the problems of those who were already lonely and whether the composition of the population most at risk of social isolation and loneliness has changed during this unprecedented period.