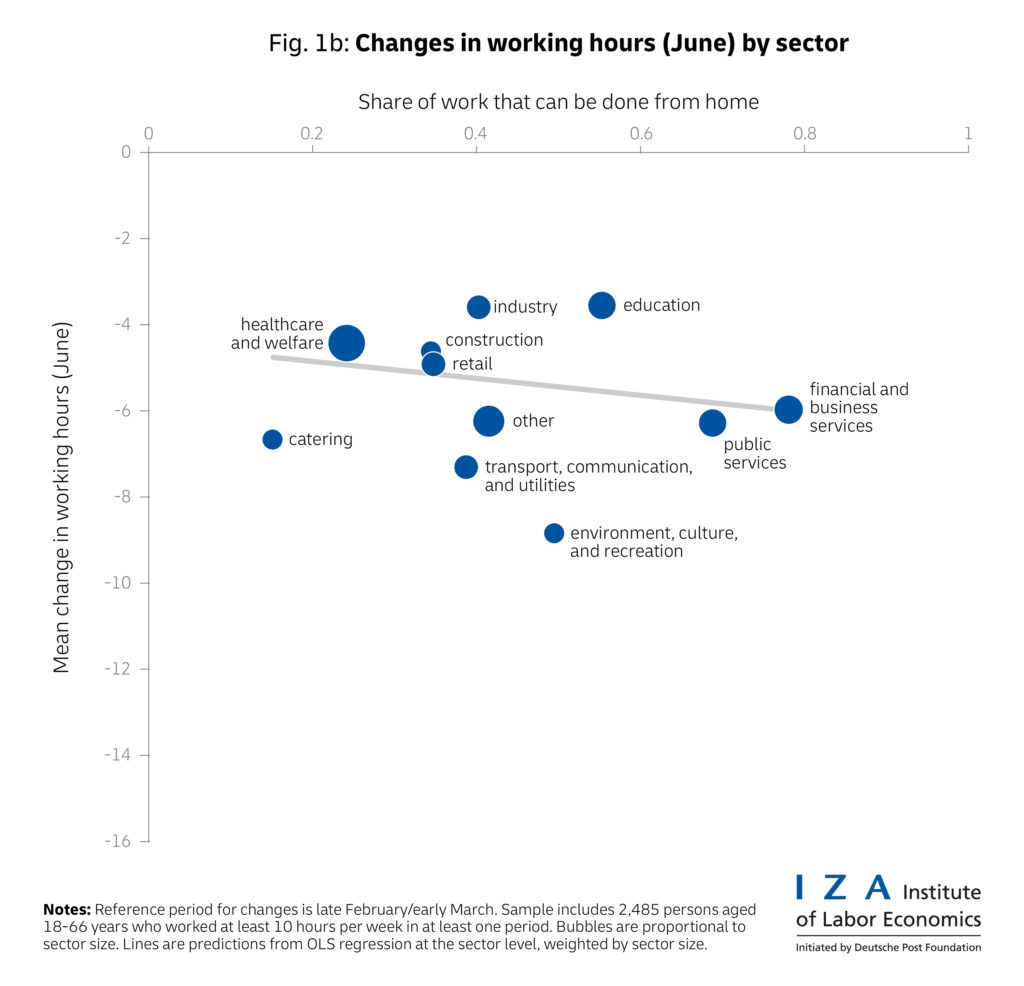

The Covid-19 pandemic has fast-tracked the adoption of flexible work modalities by employers around the word. In particular, teleworking has proven itself as an important scheme of ensuring business continuity, increased productivity, and better work-life balance.

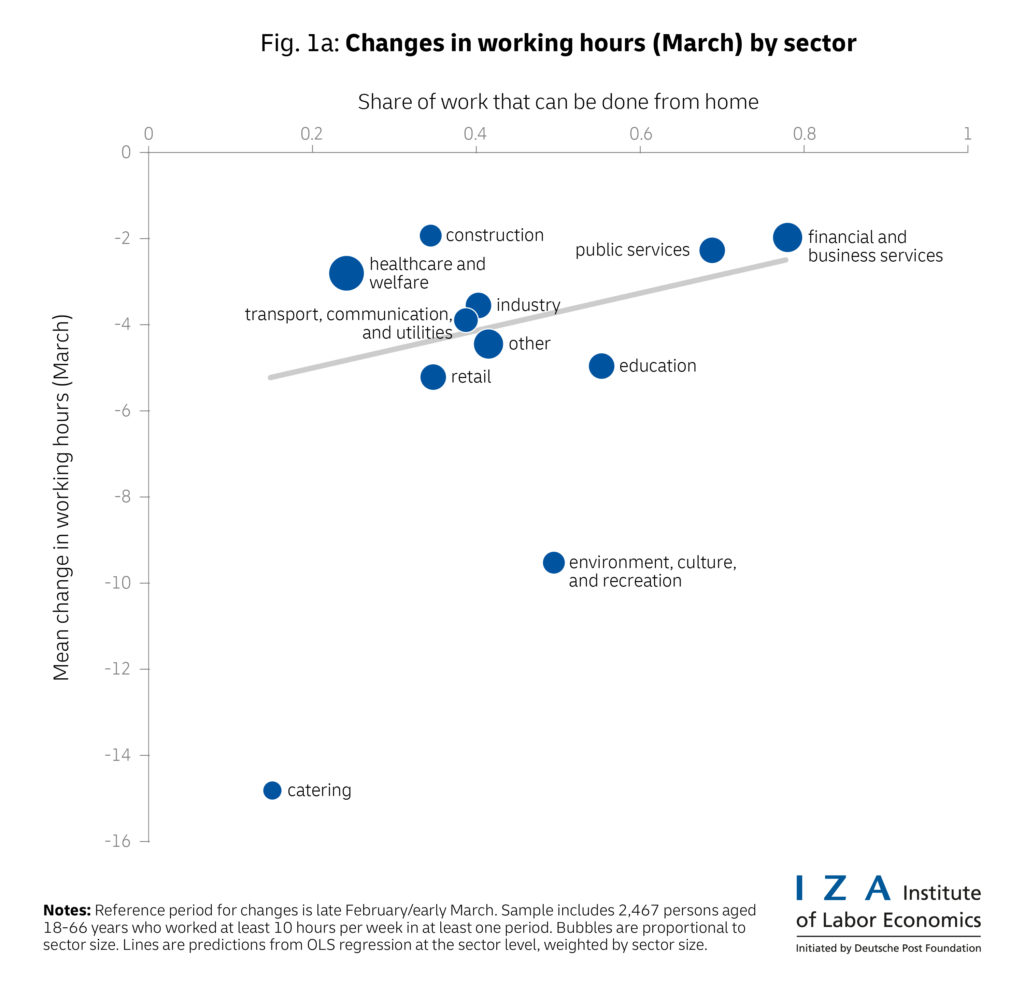

However, teleworking is only one form of job flexibility. It is mainly based on replacing the workplace with the home, while maintaining demanding characteristics in schedules and expected results. Also, teleworking is supported only for a limited number of jobs. Recent research estimates that the proportion of jobs that can be carried out from home are few, ranging from 6% in Ghana to 34% in the United States.

Pros and cons of flexible work arrangements

Teleworking also raises some concerns. By reducing interactions among workers and between workers and supervisors, there is a risk of reduced productivity, particularly in jobs where interactions are necessary. Similarly, working from home could increase distractions for workers. Finally, blurring the boundaries between work and home could lead to increased working hours and, consequently, increased employee stress levels and fatigue. In sum, teleworking affects productivity by modifying two key dimensions at the same time: the workplace and the working time schedule.

Other types of flexible work arrangements are related to schedule flexibility, such as being able to decide when to start and stop working, and the total time spent on the job – i.e. working part time. If workers value such arrangements, they are willing to work for lower wages in exchange for such flexibility. Alternatively, when keeping pay constant, the option of such autonomy may boost a worker’s productivity either by increasing their motivation or stimulating reciprocal behavior.

A key question regarding such flexible working arrangements is why firms do not offer them more often. A possible answer is that employers may worry that giving workers more freedom will cause them to work less or to reduce their level of effort. Some studies have demonstrated a net productivity-enhancing effect of work-schedule and workplace flexibility for non-routine tasks and jobs that require little coordination through interactions; yet productivity may decline for routine tasks. However, causal evidence is still scarce, especially with respect to work-schedule flexibility.

The findings are more mixed and the causal evidence even more limited for part-time work. Compared to other forms of flexibility, part-time workers could increase their productivity by suffering from less fatigue than their full-time colleagues or by allowing the more intensive use of capital. However, high fixed start-up costs imply that part-time workers may be less productive than their full-time counterparts, because the latter incur such costs for any number of hours worked. Moreover, part-time workers may be less committed to their career goals, and the returns on training may be lower.

Field experiment in Colombia

A recent IZA study by Marie Boltz, Bart Cockx, Ana Maria Diaz, Luz Magdalena Salas aims to provide causal evidence of the effects on productivity in a routine temporary job of two of the three flexible working arrangements described above: (1) working part-time and (2) being able to decide when to start and stop working within the work week. The researchers carried out a field experiment in Bogotá, Colombia’s capital city.

“Flexible work schemes can enhance productivity in two ways, they can either increase the attractiveness of the job such that intrinsically more productive workers self-select into it, or they incentivize workers to exert more effort or time to working,” says Marie Boltz. The authors aim to capture both sources and disentangle the effect into these components in a natural environment.

In order to capture the consequence of self-selection, the field experiment began from the moment the job ads for a three-week position as data entry operators were posted. The vacancy was advertised without reference to the contract environment. Applicants provided standard resume information and performed an online test in which they had to carry out similar data entry tasks as the job to which they were applying. This allowed the researchers to construct an ex ante measure of productivity and to disentangle the sorting effects on productivity from the ex post motivational effects.

Flexible contracts increase productivity by up to 50 percent

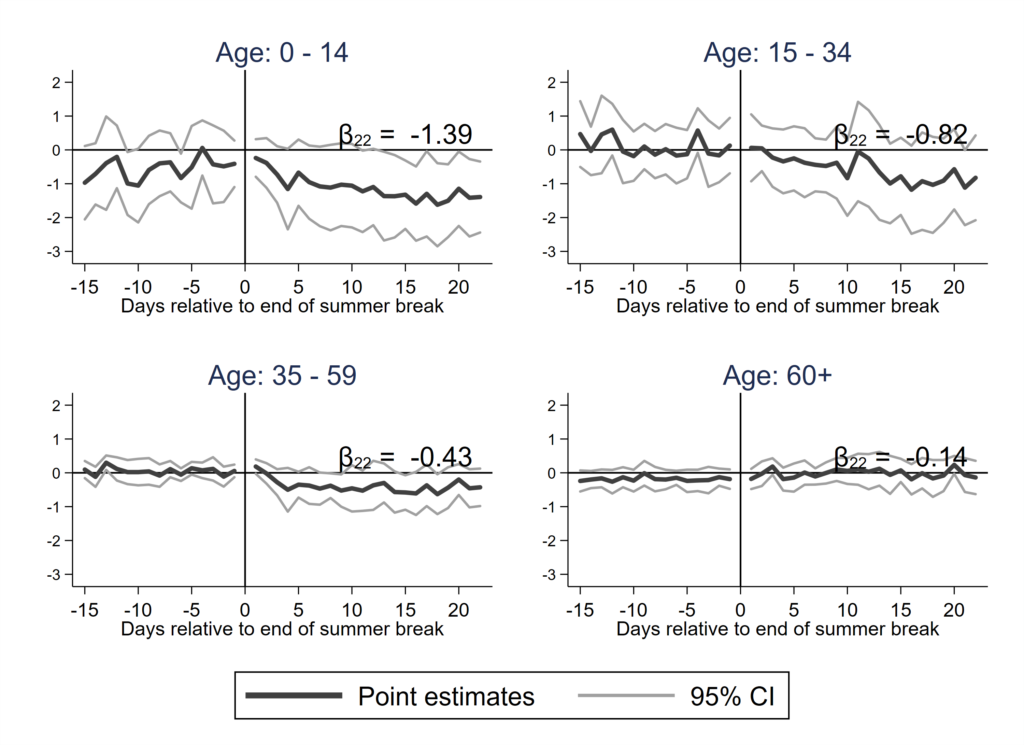

The findings suggest that an employer can increase a worker’s overall productivity by nearly 50 percent by offering a full-time flexible contract rather than a full-time non-flexible one. About 40 percent of this overall effect is attributed to attracting more productive workers. The remaining 60 percent is attributed to a motivational effect that is almost completely driven by the fact that full-time flexible workers take fewer breaks than those with non-flexible contracts. This results in a 10-percentage-point increase in effectiveness relative to contractual working time.

The paper also finds that part-time flexible and non-flexible contracts can enhance total productivity, but these effects are not significant at conventional levels. However, part-time workers, with or without a flexible time arrangement, spend 15 percentage points less time taking breaks in the workplace relative to contractual time than the reference group, and this effect is highly significant. This does not show up in the global effect on productivity because these part-time workers make more mistakes, or are more frequently absent from work.

The authors’ finding that working-time flexibility can substantially enhance productivity in a routine data entry task is new. Prior studies have argued that flexibility is especially valuable in non-routine jobs, but that the impact on productivity in routine jobs may be negative. Another contribution to the literature is that this field experiment began during the recruitment process, which allows the researchers to jointly evaluate the total productivity effect of flexible work arrangements that is induced both by attracting more productive workers and by motivating them to exert more effort.